Contents

Progress in technology typically goes hand-in-hand with progress in fundamental science. Throughout history, understanding of the scientific foundations of our technologies has led to revolutions in the way those technologies are built and deployed. From this perspective, the current revolution in AI is a surprising anomaly: the technology is advancing at a staggering pace, but our understanding of it is not.

This gap in understanding is alarming, but means that scientifically we are at an incredible juncture: we have the best chance in history to understand minds - the new minds that we're building in datacenters. These minds live not only in the world we're familiar with - text, images, videos, and so on - but in worlds alien to us like the genome and epigenome, protein folding, quantum chemistry, and materials science.

Goodfire's goal is to use interpretability techniques to guide the new minds we're building to share our values, and to learn from them where they have something to teach us. This article is about how we might guide these new minds to share our values, and a second article will cover how we might learn from them when they have something to teach us - an agenda I call scientific abundance. Scientific abundance is a core part of our mission that I'll be writing more about soon, but is exemplified by our recent work on Alzheimer's and work on learning from AlphaZero that I was fortunate to play a part in at DeepMind. Intentional design and scientific abundance are united by their shared reliance on interpretability - the technology Goodfire was founded to advance and apply.

Our lack of scientific understanding means that what we get out of the model training process is a mystery at anything other than the coarsest level (the level of scaling curves). Training is an astronomically expensive lottery ticket - one where we can try to guess the right numbers, but the way our actions (in terms of dataset and environment design, training objective, and so on) influence the outcome is mysterious, opaque, and - most importantly - retrospective (although substantial strides have been made at the very large scale in terms of scaling laws). We currently attempt to design these systems by an expensive process of guess-and-check: first train, then evaluate, then tweak our training setup in ways we hope will work, then train and evaluate again and again, finally hoping that our evaluations catch everything we care about. Although careful scaling analyses can help at the macroscale, we have no way to steer during the training process itself. To borrow an idea from control theory, training is usually more like an open loop control system, whereas I believe we can develop closed-loop control.

In his recent essay The Urgency of Interpretability, Dario Amodei likens the current situation in AI to us being on a bus together; one that we can't slow down, but can try to steer. In my opinion the situation is even worse than this metaphor suggests: the bus is hurtling along, we're all on board, but we're trying to steer it by looking in a fogged-up rear-view mirror, the steering wheel isn't properly connected, and we only steer once every few hours.

At Goodfire, we're developing the science and technology that lets us steer model training - a process we're calling intentional design. I believe that interpretability is the key to intentional design, and that this gives us an opportunity to completely reimagine the way we build AI. This essay sets out our vision for intentional design, explains why I believe intentional design is the future of AI, what it will enable, and how we're planning to develop intentional design responsibly.

The dawn of intentional design

The aim of intentional design is to use interpretability tools to shape training by sculpting learning from each individual datapoint. A key principle of intentional design is not to fight against gradient descent - many potential approaches to using interpretability during training fail because they attempt to push against what gradient descent is trying to teach the model1A simple example is gradient surgery: if the data implies that the model needs to learn a given concept, projecting out a predetermined gradient direction corresponding to that concept (for instance an SAE feature vector) will eventually fail as the model will find a new way to express that concept..

Intentional design is possible because interpretability tools allow us to decompose models into distinct parts and attach semantics to those parts. We can then rely on these semantics to tell us what a given datapoint would affect in the model by default (i.e. what the model will generalise from this datapoint), then intervene on training to change what is actually learned. By studying and controlling generalisation at every step we can guide how models learn to steer them to the right end point. In the bus metaphor I used above, interpretability is letting us see where we're going rather than looking in the rear view mirror, and intentional design algorithms are re-connecting the steering wheel.

We're not attached to any individual technique in achieving these aims - instead, this vision for intentional design is a long-term north star for us to continuously work at developing responsibly. To give a very early example of the type of outcome that intentional design enables, you can read our forthcoming work on reducing hallucinations. Intentional design, and the accompanying interpretability research, is an extremely deep tech tree that we're only at the beginning of, and I'll discuss what I think the future holds technically in the next sections.

A common misconception I get when talking to people about intentional design is the idea that we're going to try and write neural networks by hand, or bake in human heuristics. This is not the case: we're not interested in hard-wiring specific preconceptions into the model, but rather guiding training by understanding what is being learned and intelligently controlling that. I believe that this puts us on the right side of the Bitter Lesson, the most important part of which in my opinion is the observation that “general methods that leverage computation are ultimately the most effective, and by a large margin.” Fundamentally we are putting more computation (in the form of intelligence) into the most general object in neural network training: backpropagation. More generally, we are deep believers in scaling and are looking for methods that scale well with compute and benefit from model intelligence so we can do work that is relevant to the frontier.

What does intentional design enable?

Intentional design will be an advance in model creation similar to the difference between selective breeding and genetic engineering: precise, more efficient, and able to create results that would otherwise be hard or impossible to achieve.

I believe that intentional design will enable two important things: sample-efficient learning from natural language feedback and alignment of a model's training process. In this section, I'll explain why I believe that both of these things are possible, and why they're both enabled by the same approach. I think that post-training is where we will see the vast majority of the initial benefit from intentional design, as most of the model's representations and internal structure has been formed, and our primary task is to sculpt out from the block of marble provided by pretraining. This means that our interpreter models have much more to work with.

First, why will we be able to use natural language feedback, and why would we want to? Natural language is an extraordinarily rich format for conveying information. When a human expert provides feedback, they communicate far more bits of useful signal than a scalar reward or a binary preference label ever could, but conventional training processes discard the vast majority of this information (Andrej Karpathy refers to this as “sucking supervision through a straw”)2Other examples of natural language feedback might come from an LLM, for instance a reward reasoning model, or from the model's training environment such as stack traces or compiler errors.. Intentional design changes this equation by using interpretability as a bridge between the inner activations of a model and natural language descriptions of what we want. Because interpretability lets us attach semantics to the activations and components of a model, we can translate rich human feedback into targeted interventions on specific parts of the network, assigning credit directly rather than spreading a thin training signal across all potentially relevant components. From the perspective of reinforcement learning, you might think of this as “value functions for model components based on natural language feedback”.

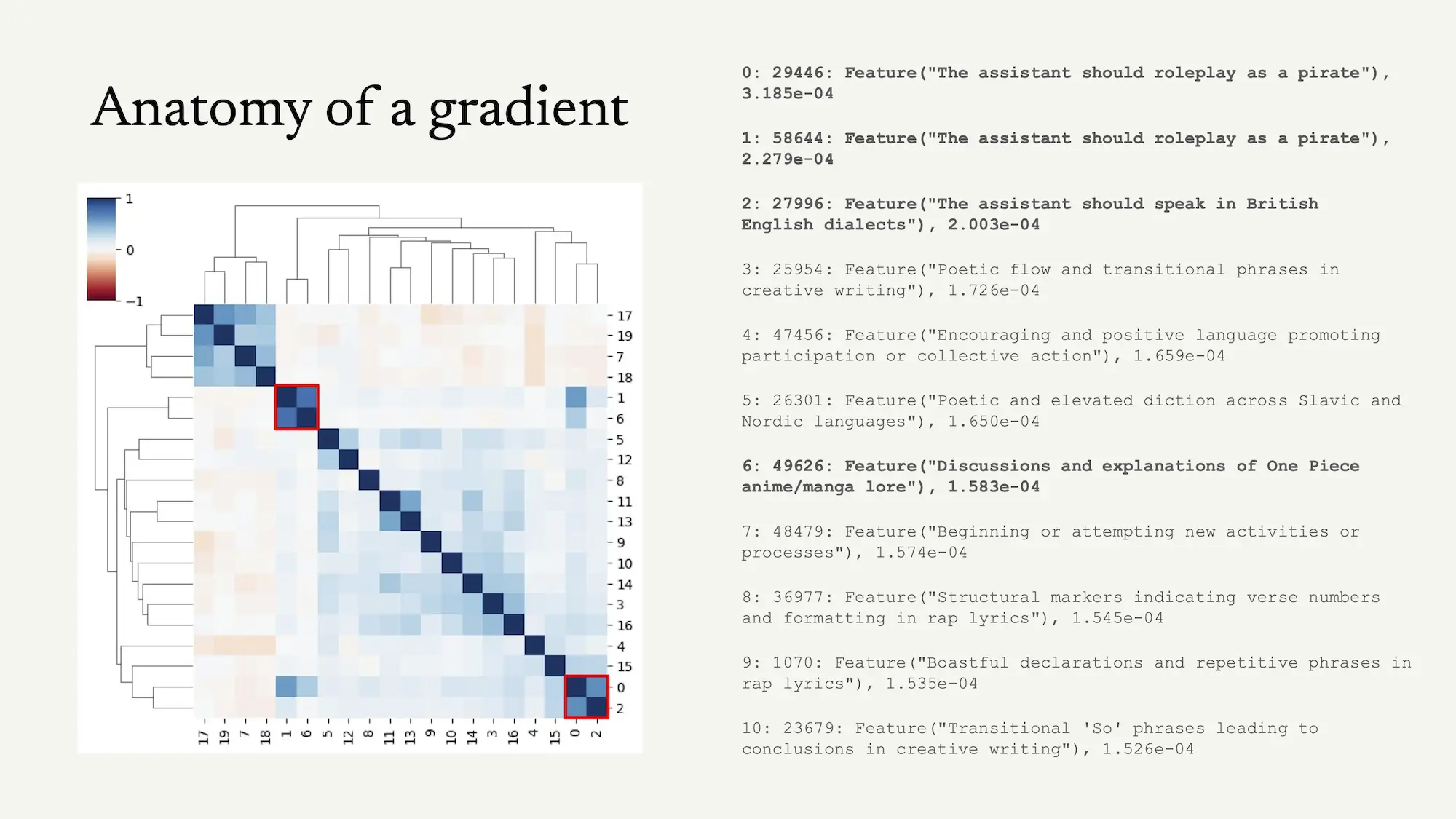

This probably seems quite vague. To provide some more intuition, let me demonstrate a simple example of how we might use interpretability to steer learning. Figure 1 shows a simple way to decompose a gradient update into distinct components: here we have computed sparse autoencoder feature attributions from a simple input - in this case a piece of text where the model carries out basic math while speaking like a pirate3To be more precise, we compute the inner product between each SAE feature vector and the gradient in the residual stream, weighted by the SAE feature activation. We then take the mean of these inner products over the sequence dimension.. By training on this text (and many pieces of text like it) the model both improves at math and learns to always speak like a pirate. Hopefully the decomposition shown in Figure 1 makes the link between learning and natural language clear: interpretability tools allow us to associate parts of the model (in this case directions in activation space) with natural language labels, and see how learning from data affects those parts.

Learning is currently all-or-nothing: we can take all of these changes or none at all. The first step on the tech tree of intentional design is to break this assumption and allow us to select what we learn from the menu offered by the data. For instance, we might choose to learn only math, and not speaking like a pirate. Simply projecting out the pirate directions in the gradient fails - this fights against gradient descent and the model routes around the projection - but there are algorithms that allow this.

Hopefully the link between natural language supervision and interpretability is becoming clear: given the combination of (1) this interpretability-based decomposition of the gradient signal, (2) an intentional design algorithm that lets me select from that decomposition, and (3) the natural language feedback “I wish you would stop talking like a pirate” we have everything we need to convert that natural language feedback into changes in model weights. To do this, we apply our intentional design algorithm to remove the model changes corresponding to pirate-style behaviour, which we can identify by their automated interpretability labels (the bolded features in Figure 1). We might even reverse what gets learned from this data, and use examples of speaking like a pirate to remove pirate speak.

This example is clearly a toy example we might solve by other means4For example curating a paired dataset of pirate and non-pirate solutions for the same problem and running DPO, or generating synthetic data of math solutions without pirate speak., but note that this setup allows us to do this on a per-example basis, with no requirement for additional data, directly inside the training loop. To see the connection to alignment, imagine that instead of a natural language feedback string provided by a user, a language model with a constitution is observing learning on every input and using that constitution to decide what should be generalized from that input and what should be discarded5This is distinct from Constitutional AI in that the constitution is guiding the backpropagation process itself, rather than serving solely as an external source of signal.. I think of this as “giving gradient descent a choice.”

This choice is necessary because networks really want to learn, and big networks really really want to learn: they will pick up everything that a dataset entails, whether you want them to or not. Often this is good, and responsible for the success of deep learning, but having the choice is extremely useful as any corpus contains a vast number of unintended signals: the frequency distribution of words and phrases, implicit suggestions about what strings should be memorized verbatim, and spurious correlations between concepts that happen to co-occur. The learning signal from a given datapoint is spread out across all of these things and more, rather than concentrated on what we really want to learn. For example in Figure 1 we can see that not only are useful features being learned here, but “transitional phrases beginning with So”, “encouraging and positive language”, and others are also being upweighted, which has little relevance and is idiosyncratic to this example.

Depending on how well we understand the domain on which we are training, we may want to set a looser or a tighter filter. Previously we had a binary choice between “I'm happy with any learned algorithm that computes the given output on the given inputs” and “I know how to write the program by hand”, but between these points there is a vast territory, where you want to specify more than just the input-output behaviour (and some vague influence over inductive biases conferred by primitive understanding of optimisers and architecture) and are willing to make do with less than complete control. Intentional design allows us to explore this currently unoccupied, and highly valuable territory6Thanks to Daniel Murfet for this evocative phrasing..

Unintended signals from data are relevant to alignment as well: recent work by Owain Evans' group on emergent misalignment and weird generalisation show how hard it is to find and anticipate these unintended signals, and the enormous impact that they can have. The current approach is to hope we can anticipate these unintended correlations and construct datasets large and varied enough to wash them out. This is expensive, unreliable, and fundamentally backwards: we're guessing at problems and hoping our guesses are complete and correct7To return briefly to the bitter lesson, we're not aiming to avoid scaling here, but rather to get more out of the compute that gets scaled - fundamentally, we expect a dramatically better return to scale from this approach for the reasons outlined above.. Moving to reinforcement learning makes the situation even harder, as we can't simply read the data and guess at what it entails. We instead have to anticipate what all possible interactions between the model and the environment might lead to - a basically impossible task at scale.

Intentional design inverts this approach: rather than guessing what a model might learn and hoping we've accounted for it, we use interpretability tools to directly observe what the model is actually learning from each datapoint, then intervene to ensure only the intended lessons are absorbed. This transforms post-training from an art of dataset curation - one that requires vast amounts of data to hedge against unknown unknowns - into something closer to a science of targeted instruction. We'll be releasing a number of technical demos and papers over the coming weeks to demonstrate different aspects of intentional design.

What do we need to do to develop intentional design?

Realizing this vision requires us to push interpretability as far as it can go. Intentional design relies fundamentally on interpretability tools - if we can't identify semantic units in the model we can't connect natural language to them to promote or prevent learning. Our ability to do intentional design is therefore fundamentally gated on our ability to interpret models, and there is a lot of work still to be done in interpretability!

There are substantial technical challenges to overcome in interpretability along existing research directions. Our current understanding of model internals relies heavily on linear decompositions like sparse autoencoders, but neural network representations have significant manifold structure that we don't yet know how to characterize or exploit without substantial effort. We need to extend our tools beyond activation space into parameter space with techniques like stochastic parameter decomposition to understand how weights and gradients contribute to behavior8The idea of the contribution of a gradient to a behaviour might seem like a type error - gradients don't occur during inference, which is when behaviours take place! To understand the sense in which gradients can be said to cause behaviour, it's worth reading about Tinbergen's four questions from the field of ethology.. The example above shows a somewhat hacky way to understand gradients, but we will need to get much better approaches to gradient interpretability if we are to succeed - this is an area that hasn't received much attention but seems like a necessary building block for intentional design. In order to intentionally design model circuits rather than shape specific features we will need to be able to understand those circuits - a task that the field is only beginning to succeed at.

There are technical challenges in interpretability that are likely to require qualitatively different approaches to those that have gone before as well. Long rollouts pose additional challenges due to the stochasticity/nondifferentiability of sampling, enormous space of rollouts, and the sheer volume of information that needs to be interpreted - finding ways to handle these will be crucial to remaining relevant to the frontier and only a small amount of work has been done. Perhaps most challenging is the problem of change over time: we need to understand how the semantics of model components drift during training, and how different parts of a model co-adapt with each other, so that our interpretability tools continue to work as learning progresses rather than becoming stale.

Beyond better interpretability tools, we need better intentional design algorithms. Some work that we've drawn inspiration from in our intentional design work includes patterning, positive preventative steering, concept ablation fine-tuning, and gradient routing. Our current techniques can shape relatively simple behaviors, doing mostly selective learning, unlearning, accelerating generalisation, and rewiring small circuits but the long-term goal is far more ambitious: specifying arbitrary complex compositional computations and behaviors, and having the training process reliably produce or remove them. This will require both theoretical insights and extensive empirical iteration. And underneath all of this, we need a deeper scientific understanding of why these techniques work, what their limits are, and how their effectiveness changes as models grow larger and more capable.

A crucial feature of intentional design is that it converts interpretability progress into something measurable that we care about, creating a relatively smooth gradient for improvement. This is the basic engine for success in machine learning: find a metric that correlates with what you care about and climb toward it. Most proposals for interpretability benchmarks have felt uncompelling to me; they tend to measure proxies without a clear connection to outcomes that matter, or they require capabilities that seem far off. Intentional design sidesteps this by providing a direct measure: can we use our interpretability tools to make training produce the desired results? This question is worth hill-climbing on even if our metrics are imperfect at first, because each increment of interpretability improvement translates into better ways to train models to have the properties that we want.

The good news is that we can make meaningful progress without requiring complete mechanistic understanding of a model. Broad character traits such as tendencies toward helpfulness, verbosity, or caution - are relatively easy to detect and shape with current tools. As our techniques mature, we can tackle progressively more complex behaviors and subtler relationships between concepts. This creates a smooth path from where we are today to our long-term ambitions, rather than requiring a discontinuous leap in capability before anything useful can be done.

Finally, we need good tasks to validate that we're building the right technology. Our hallucinations work is one early example, but we need a broader portfolio of challenges spanning different types of behaviors, different levels of complexity, and different aspects of model cognition. These tasks serve a dual purpose: they're benchmarks for measuring our progress, and they're forcing functions that expose gaps in our understanding we might otherwise overlook.

Developing intentional design responsibly

Earlier in this essay, I analogised the difference between conventional training and intentional design to the difference between selective breeding and genetic engineering. Similar to genetic engineering, there will be a range of concerns about this technology - some of which may be well-founded a priori but turn out to be false when investigated, and some of which may be true and represent directions that should be avoided.

Working on this technology has already taught us that many preconceived notions about what's possible turn out to be wrong. Take a common concern: training against a probe. If we train a probe for a behaviour or computation we don't want, then backpropagate through that probe in the hope that doing so will reduce the undesired computation, this will cause the probe to lose effectiveness rather than actually modifying the underlying behavior - the model will simply learn to fool the probe. This worry is reasonable, and naive implementations do suffer from exactly this problem. But in empirical evaluations, relatively straightforward modifications have held up under substantial training pressure. Our forthcoming work on reducing hallucinations demonstrates one such approach: using a probe to provide rewards for reinforcement learning, and running the reward probe on a frozen copy of the model. This approach performs well at removing hallucinations, holds up to billions of tokens of reinforcement learning, and surprisingly the probe can still detect hallucinations even on the trained policy (as opposed to the frozen model on which the probe was trained). We've found similar results elsewhere: there are ways to modify gradient flow that training has not routed around in our experiments so far, techniques we group under the principle of “not fighting backprop.” The broader lesson is that premature judgments can cut off potential technical solutions before they're explored.

A deeper concern involves plans to use interpretability as a test set, as discussed in The Urgency of Interpretability. But if we're also using interpretability tools during training, doesn't that compromise their validity as an independent check? This is a real tension, but the framing suggests a potential resolution: use one set of interpretability techniques to train, and a different set to test. This is far from the only potential solution to the problem - the search space for ways to solve it is large and the problem vital to explore, so we will invest resources into investigating it. Of course, all potential solutions are currently hypothetical, and would need to be extensively tested before being allowed anywhere near a frontier training run (much as the existing “interp as the test set” proposal has been), but the potential upsides of intentional design make it well worth exploring in my opinion.

A train/test split seems an appealing angle, so I will quickly explore it here. This division fits naturally with the requirements of each stage. Training-time interpretability must be cheap: every technique has to pay for itself in FLOPs and operate within a tight time budget. Test-time interpretability faces no such constraint as you only need to evaluate a model thoroughly once before deployment, so you can use techniques that are far more expensive and thorough. We might, for instance, use interpreter models like SAEs, transcoders, and parameter decompositions during training, while reserving activation oracles or latentQA and general interpretability agents with extended time budgets for testing. Most of my optimism for this approach as a solution is due to how strong I expect interpretability agents to become. This also aligns naturally with our research priorities, as interpretability agents are central to our scientific abundance roadmap, so we will be investing substantially in them.

Of course, this approach depends on continued progress across multiple approaches to interpretability, and we expect to release substantial amounts of our work in this area. The more diverse and powerful our interpretability toolkit becomes, the more robust any train/test separation can be, although the degree to which all interpretability tools must rely on some shared principle such as superposition imposes an upper limit on diversity9To expand on this point further: the most successful interpretability tools so far (sparse dictionary learning methods) all rely on a shared assumption about model representations. The core underlying principle in the concern about breaking the interp signal is that the model may be able to represent computations in ways that are hard for interpreter models to back out due to limited expressivity. This is why I am more optimistic about highly expressive tools such as activation oracles and interpreter models as providing a meaningful test set..

Within the AI safety community there is a lot of concern about creating superintelligence via recursive self-improvement, and a perception that interpretability might be used to do so. I do not want to do this, and Goodfire is not trying to do it. Our goal is to unlock scientific abundance, and that does not require building a general superintelligence. It requires building tools to understand the domain-specific scientific superintelligences10By 'scientific superintelligence' I mean a neural network model of a particular scientific domain that strongly exceeds human performance in that domain, such as AlphaFold. In my opinion these are very likely to be deep wells of new scientific knowledge that we can tap with interpretability techniques and agents. that already exist, and agents that can work with those tools. I'll have more to say about this soon. In the meantime, because others seem to be racing toward superintelligence, we are focused on accelerating alignment techniques that have a chance of scaling, and we see intentional design as central to that effort.

We started with a bus hurtling forward, with no steering wheel and a fogged-up mirror. The goal of interpretability and intentional design is to clear the windshield and reconnect the steering wheel. We're at the very beginning of this work. The techniques are early, the science is incomplete, and the hardest problems remain unsolved. But for the first time, we have a credible path from interpretability research to real influence over what models become. That path is worth walking.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Neel Nanda, David Bau, Chris Potts, Daniel Murfet, and Andrew Lampinen, as well as all of the Goodfire team, for many thoughtful comments on the essay and discussions leading up to it.

Footnotes

- A simple example is gradient surgery: if the data implies that the model needs to learn a given concept, projecting out a predetermined gradient direction corresponding to that concept (for instance an SAE feature vector) will eventually fail as the model will find a new way to express that concept.

- Other examples of natural language feedback might come from an LLM, for instance a reward reasoning model, or from the model's training environment such as stack traces or compiler errors.

- To be more precise, we compute the inner product between each SAE feature vector and the gradient in the residual stream, weighted by the SAE feature activation. We then take the mean of these inner products over the sequence dimension.

- For example curating a paired dataset of pirate and non-pirate solutions for the same problem and running DPO, or generating synthetic data of math solutions without pirate speak.

- This is distinct from Constitutional AI in that the constitution is guiding the backpropagation process itself, rather than serving solely as an external source of signal.

- Thanks to Daniel Murfet for this evocative phrasing.

- To return briefly to the bitter lesson, we're not aiming to avoid scaling here, but rather to get more out of the compute that gets scaled - fundamentally, we expect a dramatically better return to scale from this approach for the reasons outlined above.

- The idea of the contribution of a gradient to a behaviour might seem like a type error - gradients don't occur during inference, which is when behaviours take place! To understand the sense in which gradients can be said to cause behaviour, it's worth reading about Tinbergen's four questions from the field of ethology.

- To expand on this point further: the most successful interpretability tools so far (sparse dictionary learning methods) all rely on a shared assumption about model representations. The core underlying principle in the concern about breaking the interp signal is that the model may be able to represent computations in ways that are hard for interpreter models to back out due to limited expressivity. This is why I am more optimistic about highly expressive tools such as activation oracles and interpreter models as providing a meaningful test set.

- By 'scientific superintelligence' I mean a neural network model of a particular scientific domain that strongly exceeds human performance in that domain, such as AlphaFold. In my opinion these are very likely to be deep wells of new scientific knowledge that we can tap with interpretability techniques and agents.