Using Interpretability to Identify a Novel Class of Alzheimer's Biomarkers

An AI model was trained to detect Alzheimer's from blood samples. We opened it up to understand how—and found that DNA fragment length patterns dominate its decision-making. We distilled this insight into a human-interpretable classifier that generalizes better than the biomarker classes previously reported in the literature when tested on an independent cohort.

Authors

†Goodfire Research

Post by Nicholas Wang, Ching Fang, Mark Bissell, Archa Jain, Daniel Balsam, and Michael Byun

§University of Oxford

Correspondence to nick.wang@goodfire.ai and christoforos@primamente.com

Published

January 28, 2026

Contents

Introduction

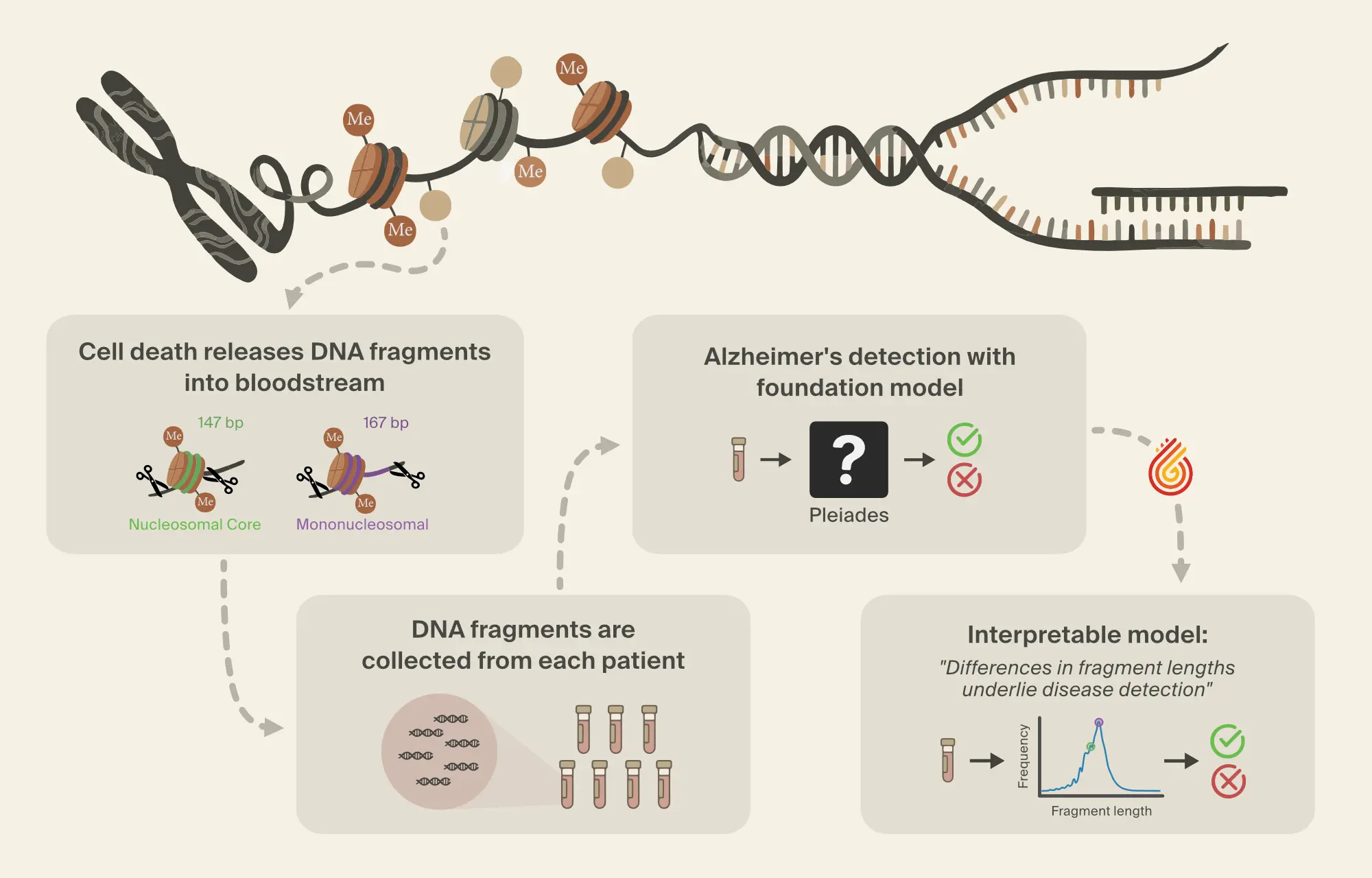

In this work, we showcase an early example of how we can translate model mechanisms into testable hypotheses. We apply our interpretability methods to Pleiades [5]Human whole epigenome modelling for clinical applications with Pleiades

Pouya Niki, Christoforos Nalmpantis, Javkhlan-Ochir Ganbat, et al., 2025. bioRxiv., Prima Mente's epigenetic foundation model, to understand how it detects Alzheimer's disease (AD) from cell-free DNA (cfDNA) in blood. In this post, we detail how we studied Pleiades to identify fragmentomics as a novel class of biomarkers for Alzheimer’s detection and conduct a pilot study on the robustness of fragmentomics for AD detection.

We test this interpretability-derived hypothesis by training a simple proxy model using only fragment length features (AUROC = 0.78, 95% CI [0.56–0.95]) and a model combined with previously reported classes of biomarkers (AUROC = 0.84, 95% CI [0.66, 0.97]) which generalize well to an independent cohort. Fragmentomics is the study of cfDNA fragmentation patterns and is an active area of research in early detection of cancer [6, 7]Early detection of multiple cancer types using multidimensional cell-free DNA fragmentomics

Hua Bao, Shanshan Yang, et al., 2025. Nature Medicine 31:2737–2745.

Genome-wide cell-free DNA fragmentation in patients with cancer

Stephen Cristiano, Alessandro Leal, et al., 2019. Nature 570:385–389., but its systematic application to AD has not been explored [8, 9]The Potential of cfDNA as Biomarker: Opportunities and Challenges for Neurodegenerative Diseases

Şeyda Aydın, Seda Özdemir, Ahmet Adıgüzel, 2025. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience 75:34.

Cell-free DNA-based liquid biopsies in neurology

Hallie Gaitsch, Robin J. M. Franklin, Daniel S. Reich, 2023. Brain 146(5):1758–1774.. Our interpretability tools identified the prominence of fragment length in Pleiades, guiding us towards its prioritization in the vast space of potential biological signals.

We are excited to continue applying interpretability analyses to increasingly capable scientific foundation models, leveraging their internal structure to accelerate hypothesis generation for disease mechanisms and the discovery of diagnostic and therapeutic targets. We envision this line of research bringing us closer to a future where humans learn about biology through studying what AI systems have learned—keeping scientific understanding, not just black-box predictive accuracy, at the forefront of progress.

Background

Pleiades: a foundation model for epigenetics

Neurodegenerative diseases, like AD, are complex pathologies with significant changes in gene regulation that cannot be detected through DNA sequences alone [10]DNA methylation signatures of Alzheimer's disease neuropathology in the cortex are primarily driven by variation in non-neuronal cell-types

Gemma Shireby, Emma L. Dempster, Stefania Policicchio, et al., 2022. Nature Communications 13:5620.. Cell identity, environmental exposures, and disease-related alterations are encoded in epigenetic marks – dynamic chemical modifications that alter chromatin structure and gene accessibility without changing the underlying DNA sequence [11]Function and information content of DNA methylation

Dirk Schübeler, 2015. Nature 517:321–326.. Key epigenetic mechanisms include cytosine methylation (the addition of methyl groups to DNA) and histone modifications (chemical changes to the proteins that organize DNA into chromatin). Recent advances in AI architectures, compute scaling, and the growing abundance of sequencing data have made it possible to build models that capture these regulatory patterns and their connections to complex disease.

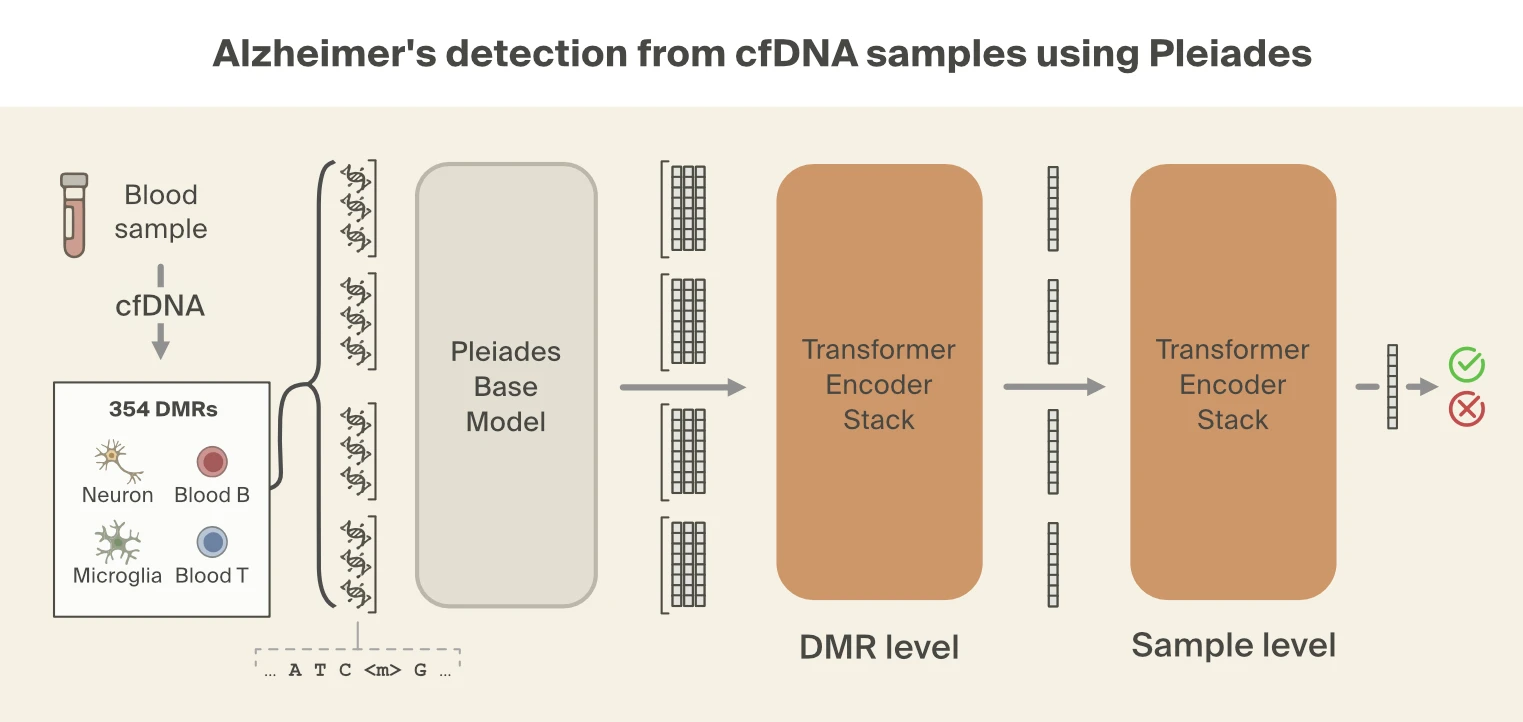

Pleiades [5]Human whole epigenome modelling for clinical applications with Pleiades

Pouya Niki, Christoforos Nalmpantis, Javkhlan-Ochir Ganbat, et al., 2025. bioRxiv. is a 7-billion parameter epigenetic foundation model trained on human methylation and genomic sequences. Data was sourced from genomic and cell-free DNA across multiple cell types and sequenced with methods that preserve cytosine methylation state. While genomic DNA provides information from the sequence itself, cfDNA also contributes another layer of epigenetic signal: fragment length profiles that reflect biological processes such as epigenetic state, nucleosome positioning and mechanism of cell death [12]Cell-free DNA comprises an in vivo nucleosome footprint that informs its tissues-of-origin

Matthew W. Snyder, Martin Kircher, Andrew J. Hill, Riza M. Daza, Jay Shendure, 2016. Cell 164(1):57–68..

The model was pretrained on 1.9 trillion tokens from this combined dataset. Tokens represented either individual nucleotides or the presence of a methyl group. Training proceeded in two stages: pretraining on next-token prediction, followed by additional training on a reconstruction task. These complementary training objectives encourage the model to learn rich, higher-order biological representations that capture complex patterns in methylation and genomic context. The resulting model can generate realistic epigenetic DNA sequences, identify cell-types of origin, and be used to integrate information across sequences within a sample.

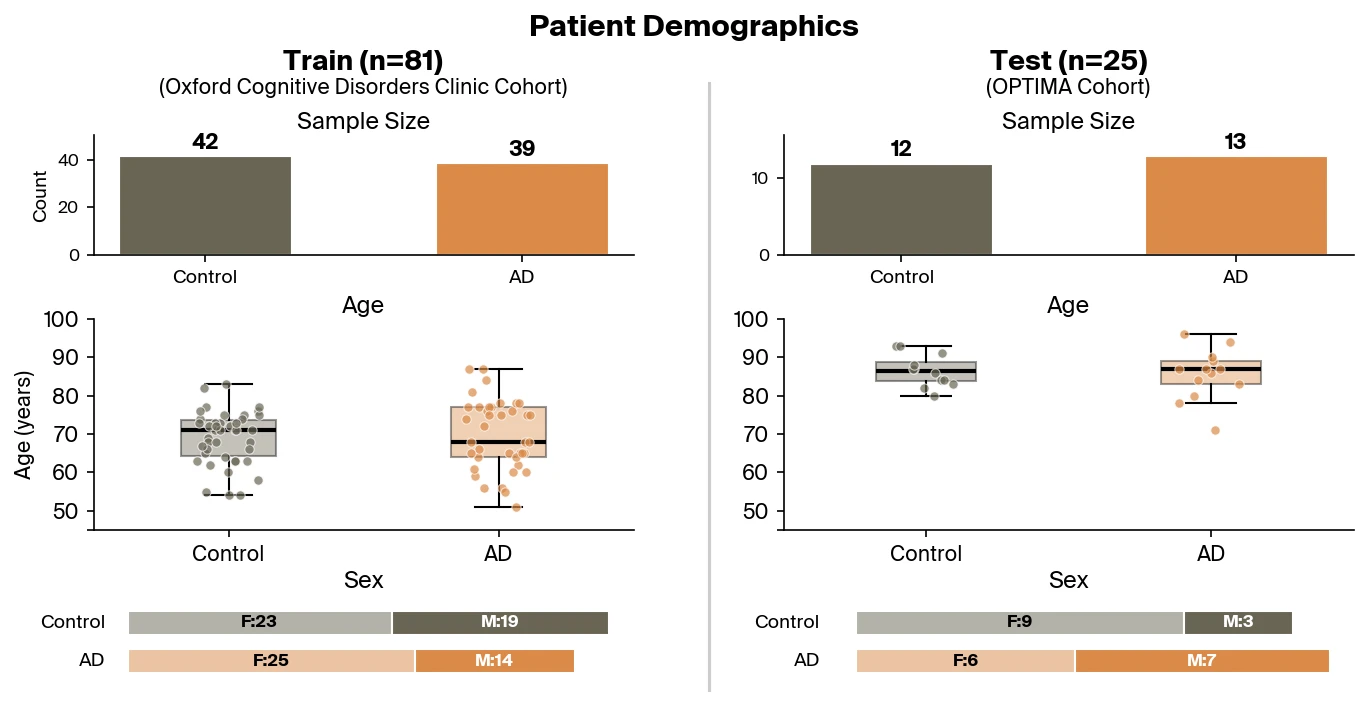

Pleiades embeddings enable accurate detection of neurodegenerative disease from blood

Pleiades can also be applied to the detection of neurodegenerative disease by leveraging its internal representations in a downstream classifier. Here, we focus on the use of Pleiades to detect AD. To train the classifier, researchers from Prima Mente sourced data from an Oxford University study with over 30 billion cfDNA fragments across a cohort of 81 individuals. Approximately half of these individuals were clinically diagnosed with AD. Importantly, AD patients and controls were well matched across age and sex. Our independent test set contains 25 individuals from the OPTIMA cohort differing primarily in age, diagnostic method, and any sample collection or sequencing batch effects.

cfDNA was extracted from blood samples provided by each patient. Each blood sample contains millions of cfDNA fragments, from which fragments that overlapped with differentially methylated regions (DMRs) [13, 14]A DNA methylation atlas of normal human cell types

Netanel Loyfer, Judith Magenheim, Agnes Peretz, et al., 2023. Nature 613:355–364.

Single-cell DNA methylation and 3D genome architecture in the human brain

Wei Tian, Jingtian Zhou, Anna Bartlett, et al., 2023. Science 382(6667):eadf5357. were used for downstream modeling. Specific DMRs were selected, restricting focus to regions of the genome where methylation patterns differed in cell types relevant to AD.

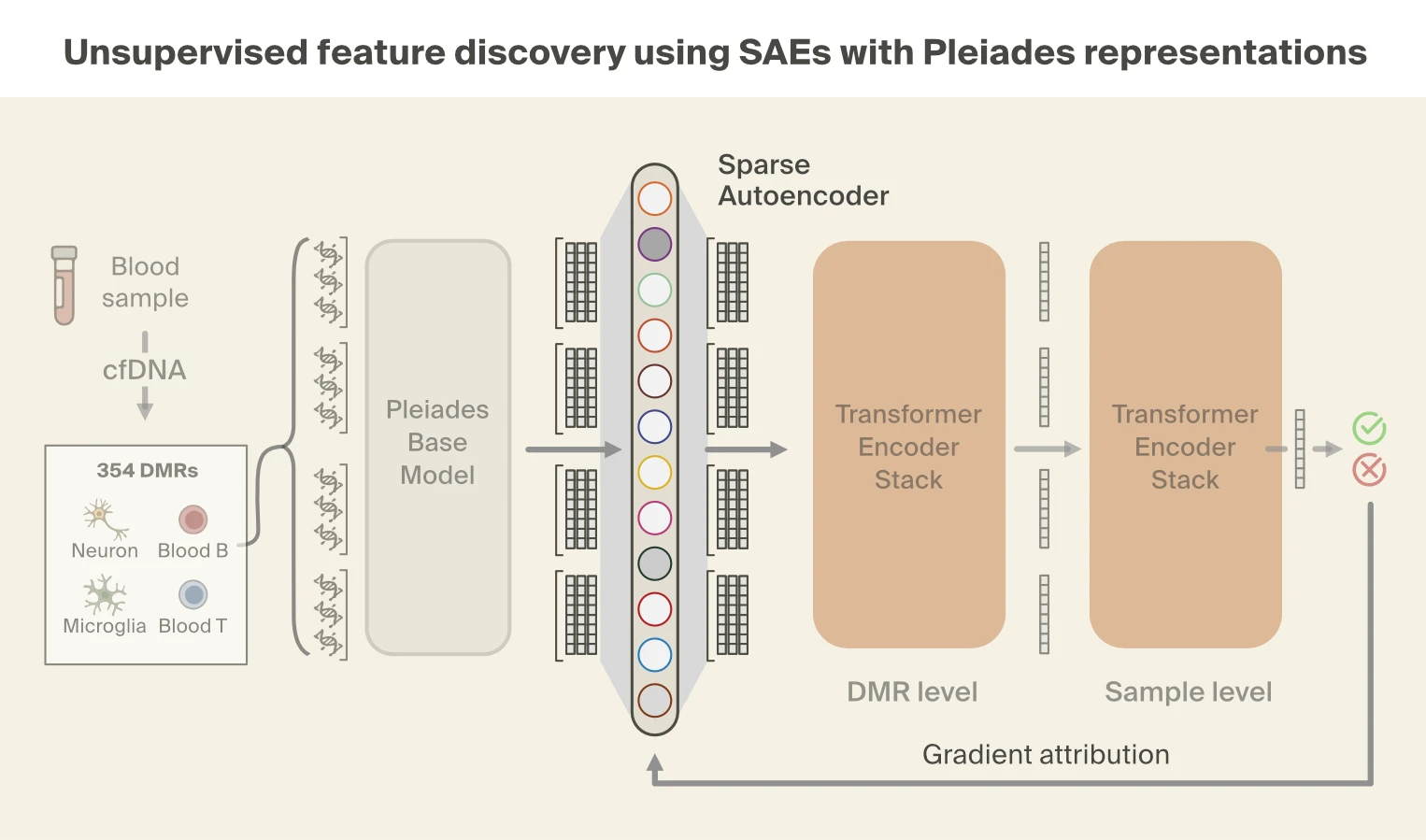

Despite this filtering process, the number of fragments per individual is still large. To combine information across fragments, the Prima Mente team used a hierarchical attention transformer to predict AD. The first level of the hierarchical classifier aggregates Pleiades embeddings from cfDNA fragments into a single embedding per DMR. The second level aggregates DMR embeddings into a single patient-level embedding which is then used for the final classification. Using this approach, Pleiades can successfully predict AD using cfDNA sequences from a blood sample with performance comparable to leading proteomic biomarkers.

Results

Interpreting Pleiades suggests fragment length and methylation as dominant signals

While the performance of Pleiades is impressive, we want to understand how the model makes its predictions for this task. To achieve this, we used our interpretability platform to study the model's behavior. We first identify which biological signals are present in its representations using both a supervised and unsupervised approach.

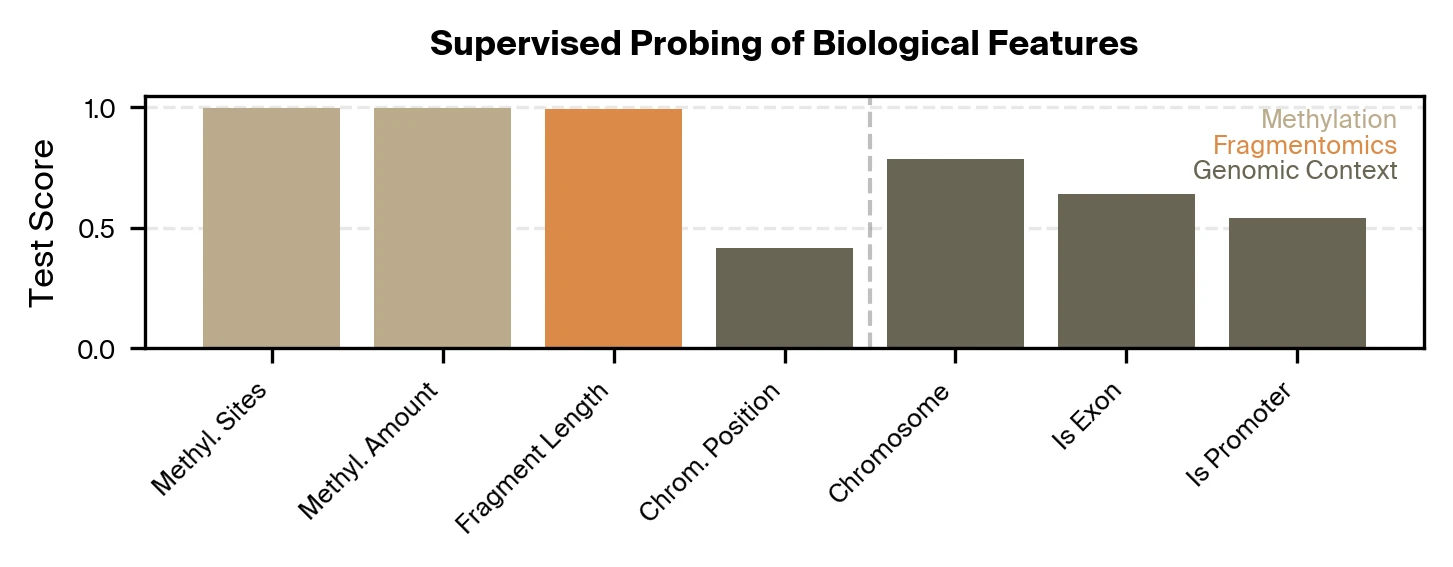

For our supervised approach, we train lightweight probes to test if specific biological signals can be extracted from Pleiades embeddings for single DNA fragments. We focus on representations from the last layer of Pleiades used by the final disease classifier. We find that these representations accurately encode fragment-level methylation and length, but recover comparatively less about genomic locus and region identity.

While supervised probing tells us what biological signals are accessible in Pleiades' representations, it doesn't tell us which signals the model actually relies on for disease prediction. To answer that question, we turned to sparse autoencoders (SAEs), which let us decompose the model's representations and trace which components drive the disease classification.

Sparse autoencoders decompose model representations into distinct "features", or concepts. As before, we focus on the representations from the last layer of Pleiades and train a BatchTopK SAE [15]Batchtopk sparse autoencoders

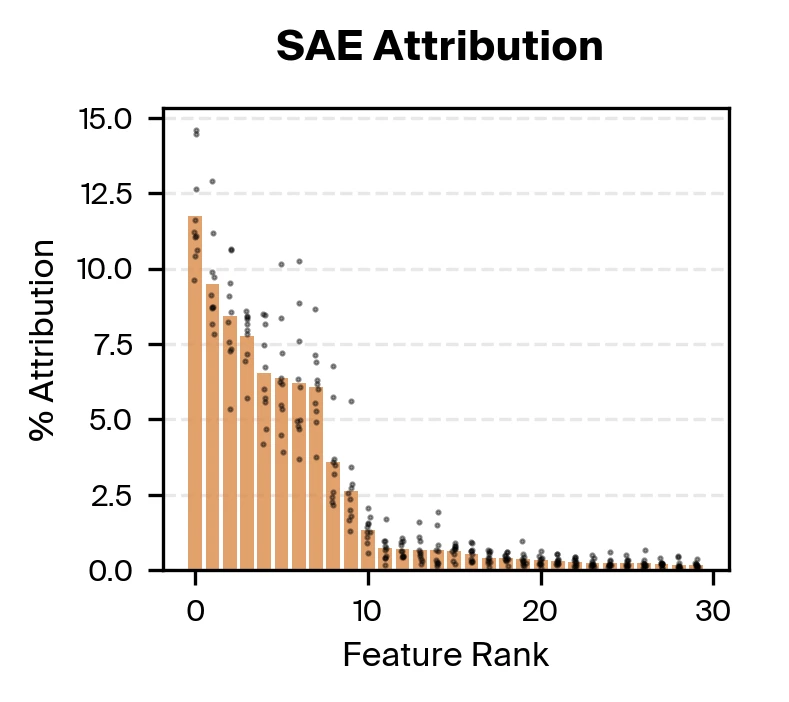

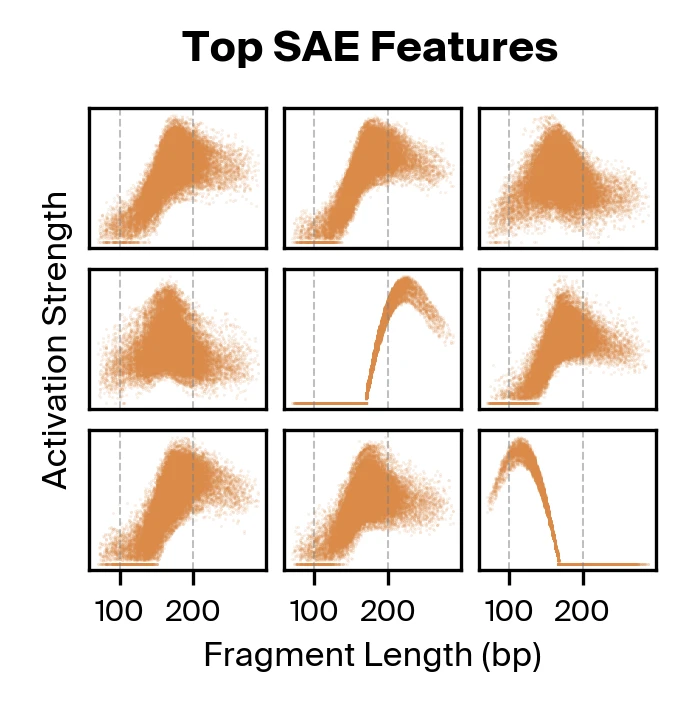

Bart Bussmann, Patrick Leask, Neel Nanda, 2024. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.06410. on the cfDNA pretraining data. We then use gradient attribution to identify nine SAE features responsible for the majority of disease classification performance. We find that these top features are all strongly correlated with fragment length.

Taking both supervised and unsupervised approaches together, we find that methylation and fragmentomics signals are accessible in the model, with fragment length taking a particularly prominent role.

Pleiades embeddings contain an informative manifold for key features

Existing literature has tied AD to differences in methylation patterns [10]DNA methylation signatures of Alzheimer's disease neuropathology in the cortex are primarily driven by variation in non-neuronal cell-types

Gemma Shireby, Emma L. Dempster, Stefania Policicchio, et al., 2022. Nature Communications 13:5620., but not fragment length, so it was unexpected to see fragment length emerge as the dominant signal. Moreover, the different activation strength profiles found in our SAE features suggests there may be additional complexity in the way fragment length is encoded by Pleiades. These findings motivated us to explore fragment length representations in Pleiades more deeply to identify specific fragmentomic features used for disease classification.

From prior literature [12]Cell-free DNA comprises an in vivo nucleosome footprint that informs its tissues-of-origin

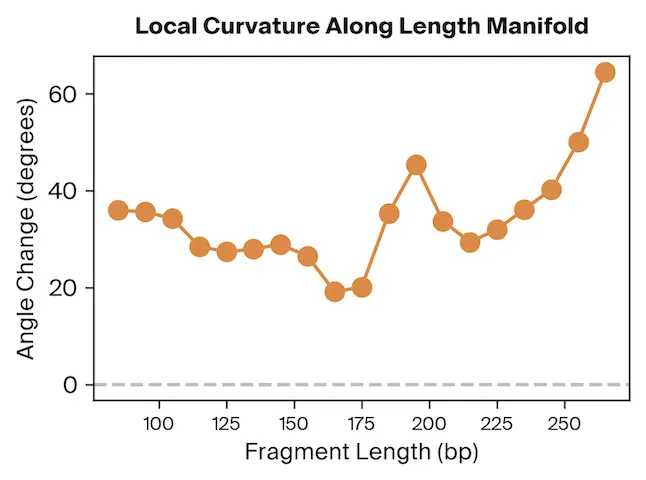

Matthew W. Snyder, Martin Kircher, Andrew J. Hill, Riza M. Daza, Jay Shendure, 2016. Cell 164(1):57–68., we know that specific fragment lengths have biological significance – for instance, 167 base pairs (bp) is the classic mononucleosomal fragment length of DNA wrapped around a single nucleosome core with linker DNA. Does the fragment length manifold found in Pleiades show differential structure for significant fragment lengths?

To test this, we project Pleiades fragment embeddings into a 3D PCA space and observe a well-defined manifold. Fragment length maps smoothly onto a U-shaped trajectory from which we measure local curvature to identify regions that are encoded with different precision than others. We find several privileged fragment length values in the representation manifold, some of which correspond to known lengths with biological significance – most notably the minimum curvature around the mononucleosomal length at 167 bp (nucleosomal core with linker DNA) [12]Cell-free DNA comprises an in vivo nucleosome footprint that informs its tissues-of-origin

Matthew W. Snyder, Martin Kircher, Andrew J. Hill, Riza M. Daza, Jay Shendure, 2016. Cell 164(1):57–68.. These points give us possible ranges of fragment lengths that the model may devote additional representation capacity to, perhaps in a way that downstream classifiers can take advantage of.

Distilling model performance to an interpretable classifier

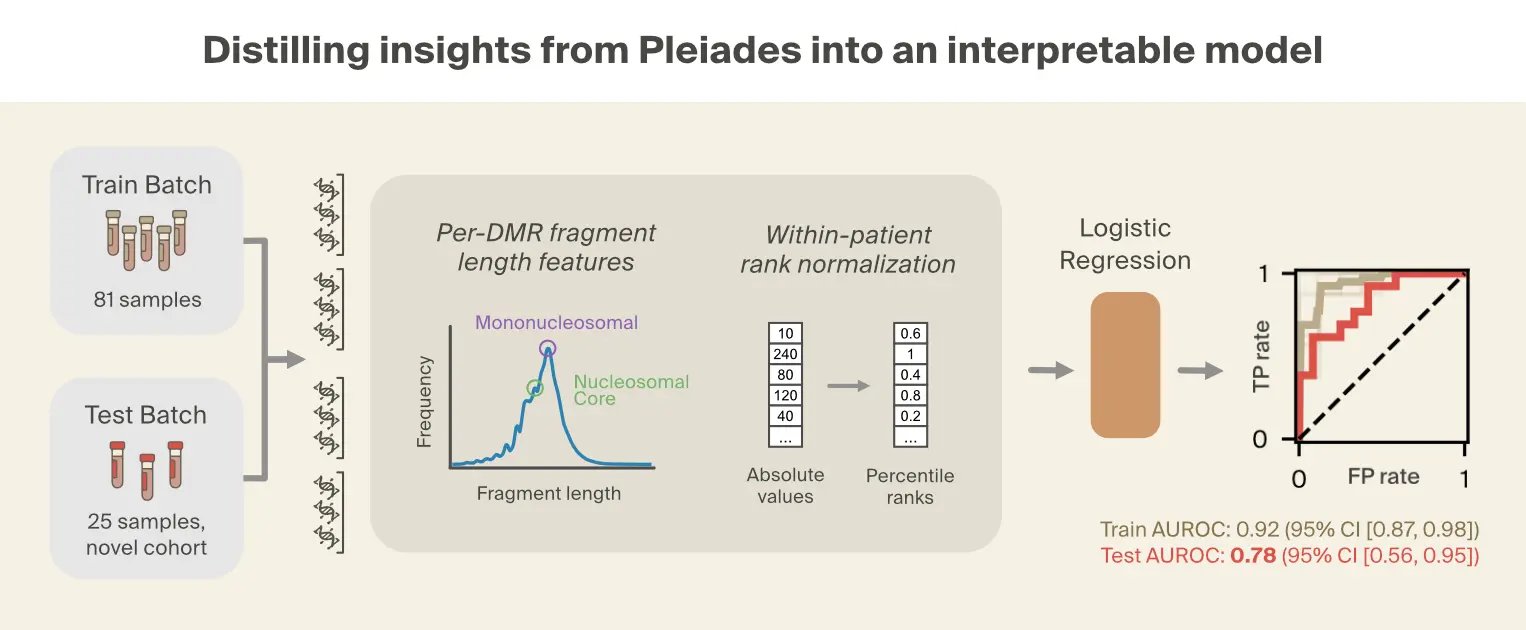

Having identified fragmentomic patterns as key to Pleiades' disease detection capabilities, we next asked whether these mechanistic insights could be distilled into a simpler logistic regression model. This approach tests whether the representations learned by Pleiades can be approximated by explicit biological features.

Based on the prominence of fragment length patterns in our interpretability analysis and prior literature [6]Early detection of multiple cancer types using multidimensional cell-free DNA fragmentomics

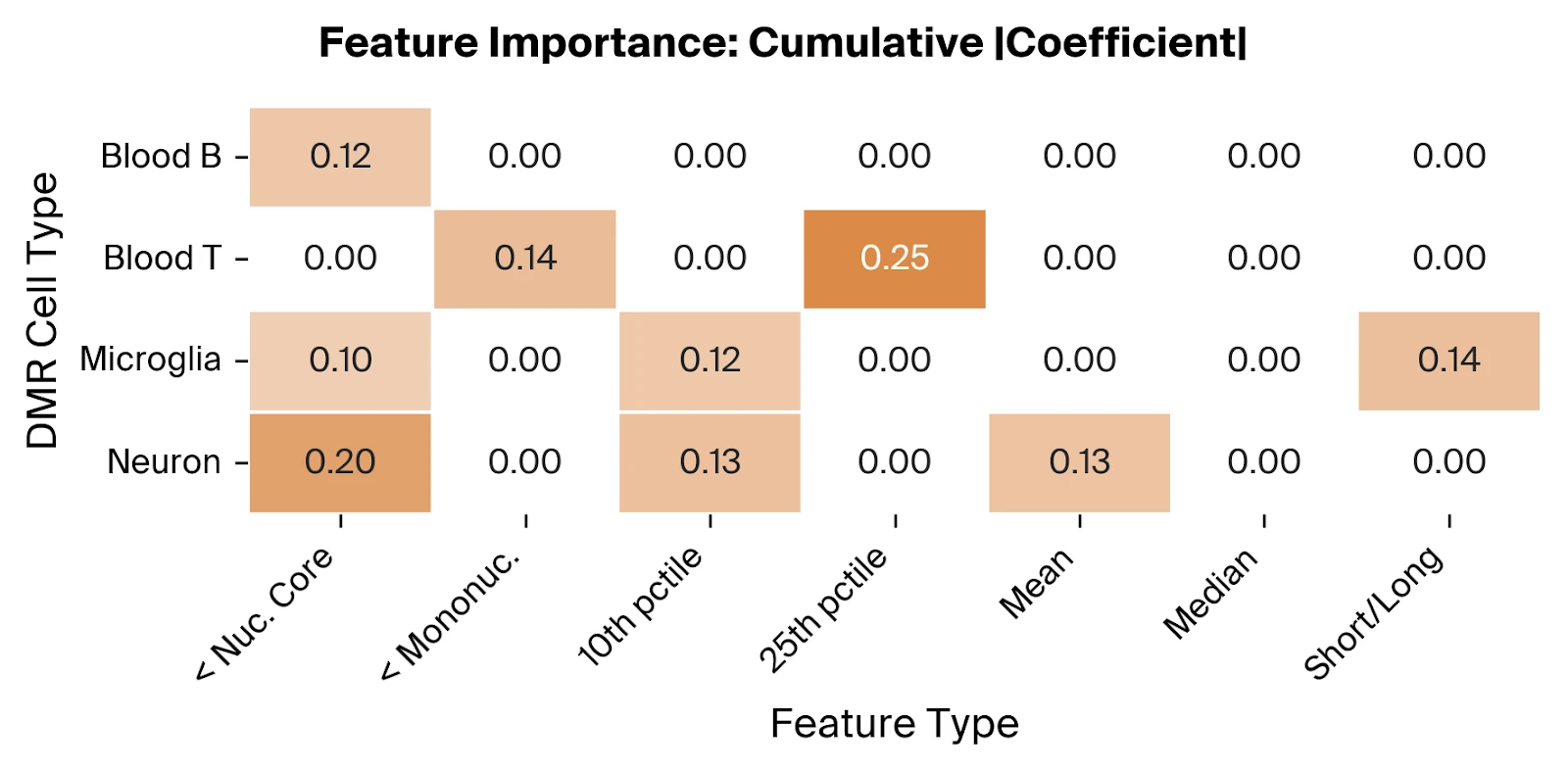

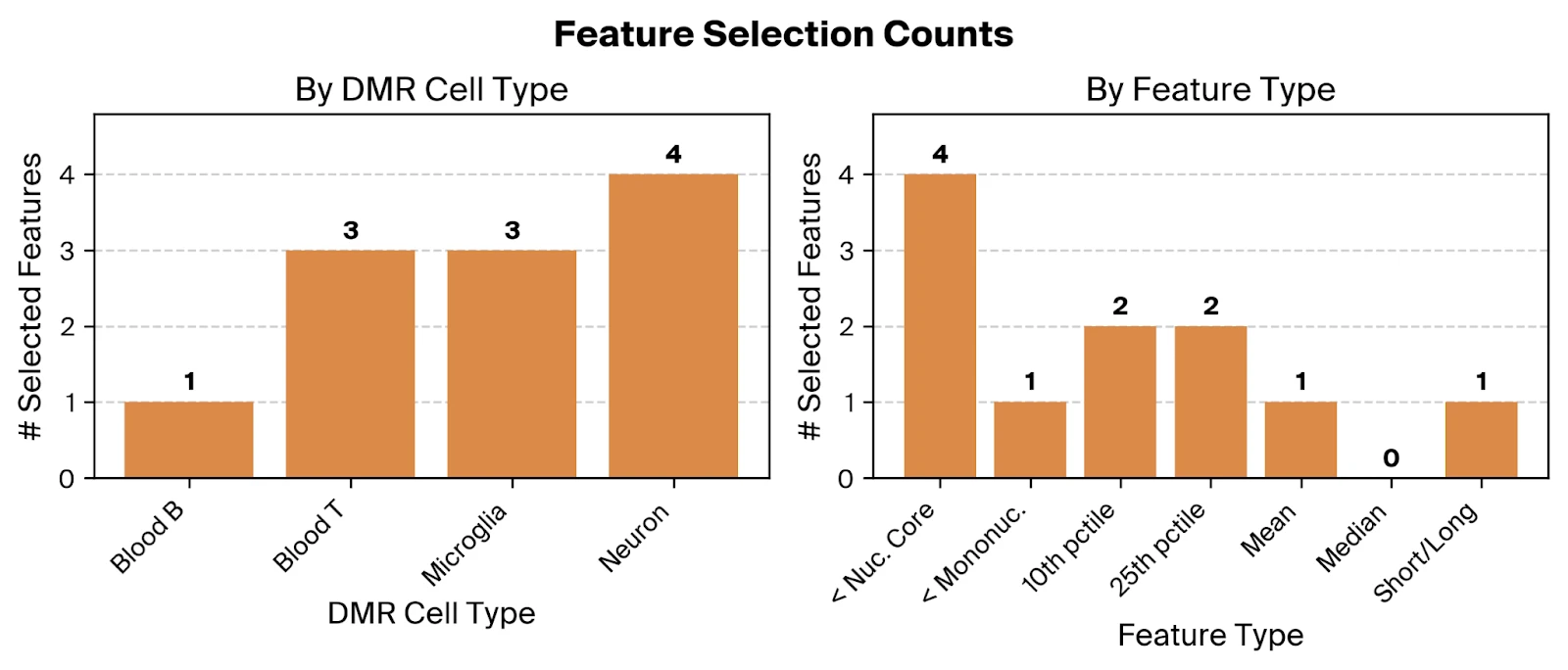

Hua Bao, Shanshan Yang, et al., 2025. Nature Medicine 31:2737–2745. linking truncated cfDNA fragments to disease states, we focused on seven fragment length metrics computed across 354 DMRs from four relevant cell types. These metrics capture both distributional properties (mean, median, percentiles) and fractions of fragments in the biologically relevant size ranges visible from the Pleiades manifold. To mitigate batch effects, each feature type was rank-normalized across all DMRs within each individual, converting absolute measurements into relative rankings.

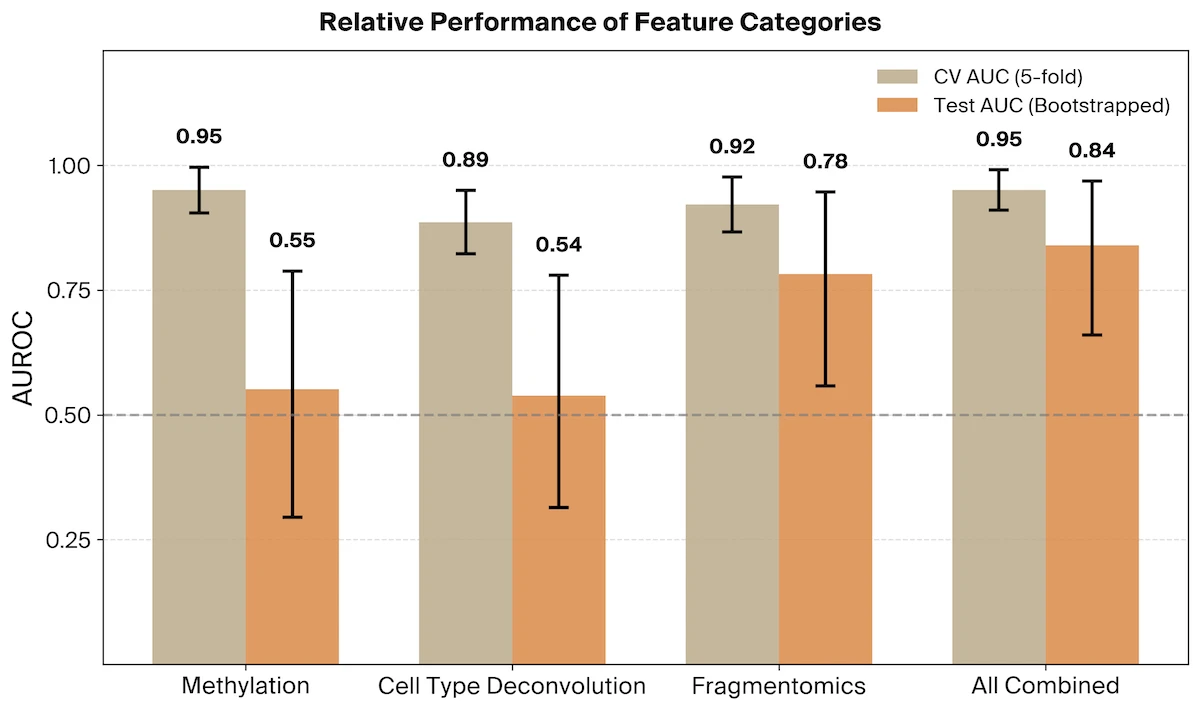

Given the small dataset, we performed feature selection over 100 bootstraps of the training set, identifying features with consistent discriminative power across dataset samples. Features selected in at least 90% of bootstraps were retained for the final model, resulting in 11 total features out of 2478 candidate features, where each feature is a specific DMR-metric combination. The resulting logistic regression model achieved strong performance on the training set with moderate generalization to the independent OPTIMA cohort (AUROC = 0.78, 95% CI [0.56, 0.95]).

Across the selected features, we find relevant contributions from all four included cell types, suggesting that altered cfDNA profiles from both neural and immune cells are predictive of AD. The overrepresentation of the '< Nucleosomal Core' feature type, using Pleiades-derived thresholds consistent with nucleosome biology, supports the hypothesis that truncated fragments from dysregulated epigenetic states are disease associated.

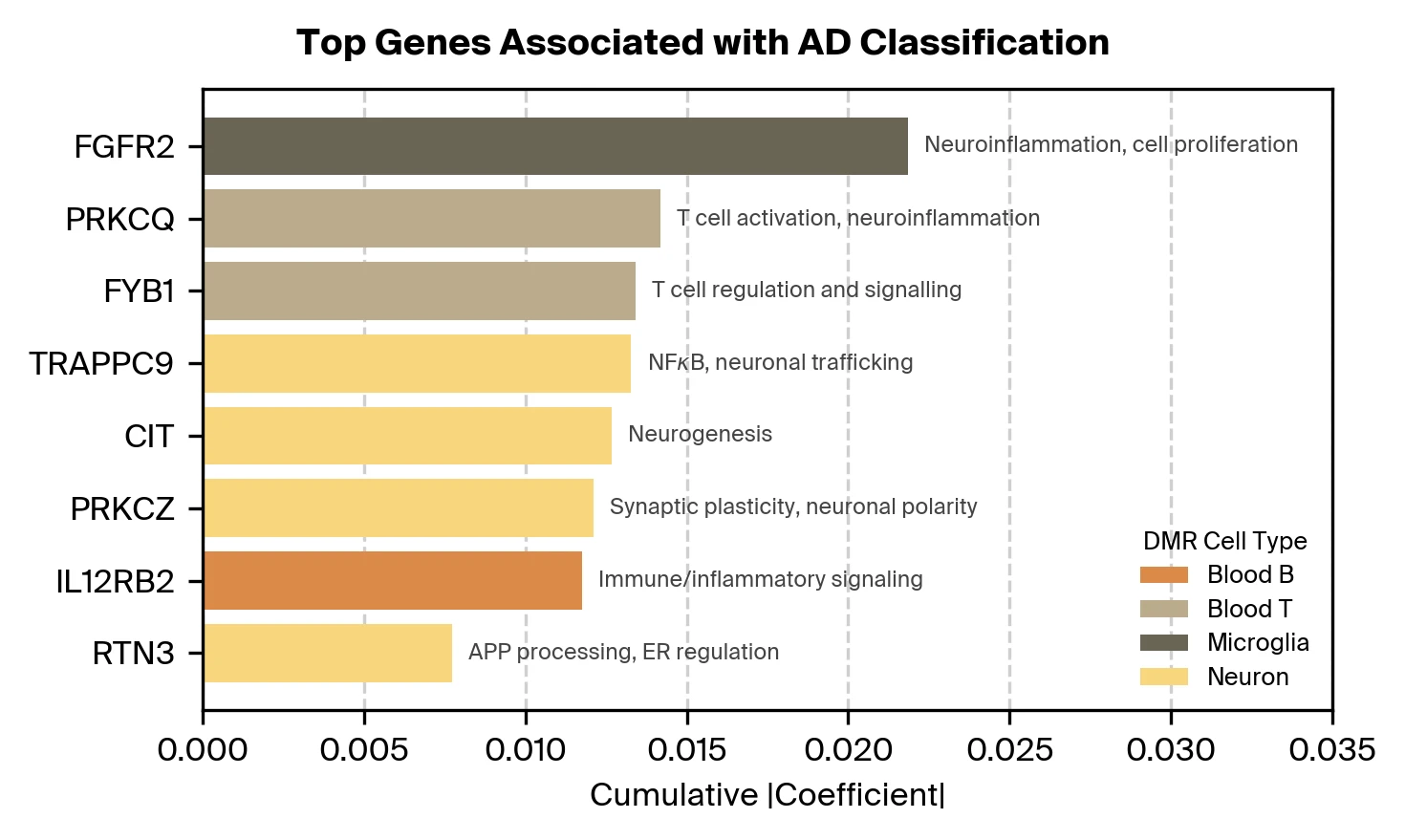

Our feature selection process also identifies informative DMRs. What genes are these DMRs regulating? We aggregate DMRs by nearby genes (within 10k base pairs) and find associations with genes plausibly related to AD as well as known risk genes. Further investigation is needed to confirm whether these DMRs functionally regulate the identified genes and to establish their causal relevance to AD pathology.

Fragment length generalizes better to an independent cohort and is complementary to previously reported predictors

To compare with previously reported predictors [16, 17]Artificial intelligence and circulating cell-free DNA methylation profiling: Mechanism and detection of Alzheimer's disease

Ray O. Bahado-Singh, Uppala Radhakrishna, et al., 2022. Cells 11(11):1744.

Circulating Cell-Free DNA Methylation Profiles Enable Disease-Specific Detection of Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and ALS from Blood

Chad Pollard, Erin Saito, et al., 2025. medRxiv., we applied an identical feature selection pipeline using features derived from methylation patterns and cell type deconvolution. Methylation patterns include statistics such as the mean and standard deviation of methylation rates across fragments in a DMR– variables we know are represented in Pleiades from our probing experiments.

Cell type deconvolution methods tell us what percentage of fragments that intersect with a particular DMR come from that DMR's associated cell type. We implement cell type deconvolution with a methylation-based approach, comparing observed DMR methylation rates to previously reported methylation rates across a cell type atlas [13, 14]A DNA methylation atlas of normal human cell types

Netanel Loyfer, Judith Magenheim, Agnes Peretz, et al., 2023. Nature 613:355–364.

Single-cell DNA methylation and 3D genome architecture in the human brain

Wei Tian, Jingtian Zhou, Anna Bartlett, et al., 2023. Science 382(6667):eadf5357..

Together, these feature types look for altered methylation states and the enrichment of cfDNA fragments from cell types experiencing elevated levels of cell death. We find that for classifiers trained on methylation (AUROC = 0.55, 95% CI [0.29, 0.79]) or cell type deconvolution (AUROC = 0.54, 95% CI [0.31, 0.78]) features alone, neither generalized well across cohorts.

Finally, we evaluated a mixed model which combines all three feature categories. We find that while methylation and cell type deconvolution signals do not generalize on their own, these feature categories are additive with the fragmentomic signal yielding a final AUROC of 0.84 (95% CI [0.66, 0.97]).

A mixed fragmentomic and methylation model achieved comparable performance (AUROC = 0.84, 95% CI [0.67, 0.99]), as did a model combining fragmentomic and cell type deconvolution features (AUROC = 0.83, 95% CI [0.65, 0.96]).

To determine whether the signal we found is specific to AD and not a more general neurodegenerative signal, we tested our final classifier on a Parkinson's Disease dataset and find that the classifier does not generalize (AUROC = 0.51, 95% CI [0.41, 0.62]), indicating the potential for differential diagnoses.

Limitations

This is an early proof-of-concept demonstrating the potential of interpretability-guided biomarker discovery. Some limitations of this work include:

Sample size and cohort diversity. Our analysis is based on 81 patients from a single Oxford University cohort. While our test set was from an independent cohort (OPTIMA), this remains a small sample from a limited demographic and geographic context. Effects that appear robust here will require validation across larger, more diverse populations; presently our confidence intervals on classifier performance are wide due to limited statistical power.

Interpretability-to-biology gap. Interpretability tells us what features drive the model's predictions, not whether those features reflect underlying disease biology or artifacts of data collection. Fragment length may be predictive because it tracks real pathology, or because it correlates with confounders. Establishing a biological mechanism requires experimental validation that is beyond the scope of this work.

Discussion

Our interpretability analysis pointed to fragmentomic features—particularly fragment length distributions—as central to Pleiades' disease detection. This was not what we expected based on existing literature.

The supervised probing experiments confirmed that Pleiades encodes both methylation and fragmentomic information. But when we used sparse autoencoders and gradient attribution to identify which features actually drive disease classification, fragment length dominated. Approximately nine SAE features were responsible for the majority of the classifier's decisions, with these features primarily encoding fragment length with varying specificity.

The geometry of Pleiades' embeddings reinforced this finding. Fragment lengths form a U-shaped manifold, with curvature peaks at biologically meaningful values: 147 bp (nucleosome core) and 167 bp (with linker DNA). The model appears to devote additional representational capacity to these lengths—suggesting they may be especially informative for downstream tasks.

We tested this by building a proxy model using only the fragmentomic features our analysis identified. The model generalized to an independent cohort with 0.78 AUROC (95% CI: 0.56–0.95). Adding methylation and cell type deconvolution features improved performance to 0.84 AUROC (95% CI: 0.66- 0.97). By contrast, methylation or cell type deconvolution features alone showed very little signal when testing across cohorts.

We came into this analysis expecting methylation-based features to be the dominant signal, given its emerging prominence in cfDNA and AD research [16, 17]Artificial intelligence and circulating cell-free DNA methylation profiling: Mechanism and detection of Alzheimer's disease

Ray O. Bahado-Singh, Uppala Radhakrishna, et al., 2022. Cells 11(11):1744.

Circulating Cell-Free DNA Methylation Profiles Enable Disease-Specific Detection of Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and ALS from Blood

Chad Pollard, Erin Saito, et al., 2025. medRxiv.. Studying Pleiades suggested something different. This motivated us to prioritize fragmentomic features, which showed more robust performance across our cohorts than previously reported features.

This is the contribution we want to highlight: interpretability as a tool for hypothesis triage. Foundation models learn from data at a scale humans can't match. If we can inspect what they've learned we can use that to guide experimental priorities, turning AI models into a source of testable hypotheses rather than a black box.

The results presented here are on small datasets with validation in larger cohorts underway. We hope this offers a case study of how we can use interpretability to surface candidate signals, build simple models to test them, and let the results inform the next round of experiments - both in the lab and in silico.

As biological models become more capable, it becomes increasingly important that our understanding of them keeps pace. Interpretability is how we keep scientific understanding, reproducibility, and human agency at the center of an AI-accelerated future. Our goal is to make model internals a practical source of hypotheses, so that the next generation of breakthrough technology is not only accurate, but also legible, testable, and actionable.

References

- Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold [link]

John Jumper, Richard Evans, Alexander Pritzel, Tim Green, Michael Figurnov, Olaf Ronneberger, Kathryn Tunyasuvunakool, Russ Bates, Augustin Žídek, Anna Potapenko, Alex Bridgland, Clemens Meyer, Simon A. A. Kohl, Andrew J. Ballard, Andrew Cowie, Bernardino Romera-Paredes, Stanislav Nikolov, Rishub Jain, Jonas Adler, Trevor Back, Stig Petersen, David Reiman, Ellen Clancy, Michal Zielinski, Martin Steinegger, Michalina Pacholska, Tamas Berghammer, Sebastian Bodenstein, David Silver, Oriol Vinyals, Andrew W. Senior, Koray Kavukcuoglu, Pushmeet Kohli, Demis Hassabis, 2021. Nature 596(7873):583–589. - Genome modeling and design across all domains of life with Evo 2 [link]

Garyk Brixi, Matthew G. Durrant, Jerome Ku, Michael Poli, Greg Brockman, Daniel Chang, Gabriel A. Gonzalez, Samuel H. King, David B. Li, Aditi T. Merchant, Mohsen Naghipourfar, Eric Nguyen, Chiara Ricci-Tam, David W. Romero, Gwanggyu Sun, Ali Taghibakshi, Anton Vorontsov, Brandon Yang, Myra Deng, Liv Gorton, Nam Nguyen, Nicholas K. Wang, Etowah Adams, Stephen A. Baccus, Steven Dillmann, Stefano Ermon, Daniel Guo, Rajesh Ilango, Ken Janik, Amy X. Lu, Reshma Mehta, Mohammad R.K. Mofrad, Madelena Y. Ng, Jaspreet Pannu, Christopher Ré, Jonathan C. Schmok, John St. John, Jeremy Sullivan, Kevin Zhu, Greg Zynda, Daniel Balsam, Patrick Collison, Anthony B. Costa, Tina Hernandez-Boussard, Eric Ho, Ming-Yu Liu, Thomas McGrath, Kimberly Powell, Dave P. Burke, Hani Goodarzi, Brian L. Hie, 2025. bioRxiv 2025.02.18.638918. - Finding the Tree of Life in Evo 2 [link]

Michael Pearce, Elana Simon, Michael Byun, Daniel Balsam, 2025. Goodfire Research. - Predicting cellular responses to perturbation across diverse contexts with State [link]

Abhinav K. Adduri, Dhruv Gautam, Beatrice Bevilacqua, Alishba Imran, Rohan Shah, Mohsen Naghipourfar, Noam Teyssier, Rajesh Ilango, Sanjay Nagaraj, Mingze Dong, Chiara Ricci-Tam, Christopher Carpenter, Vishvak Subramanyam, Aidan Winters, Sravya Tirukkovular, Jeremy Sullivan, Brian S. Plosky, Basak Eraslan, Nicholas D. Youngblut, Jure Leskovec, Luke A. Gilbert, Silvana Konermann, Patrick D. Hsu, Alexander Dobin, Dave P. Burke, Hani Goodarzi, Yusuf H. Roohani, 2025. bioRxiv 2025.06.26.661135. - Human whole epigenome modelling for clinical applications with Pleiades [link]

Pouya Niki, Christoforos Nalmpantis, Javkhlan-Ochir Ganbat, Donal Byrne, Husam Babikir, Anjeet Jhutty, Will Rowe, Timing Liu, Netanel Loyfer, Sofia Toniolo, Masud Husain, Sanjay G. Manohar, Sian A. Thompson, Ivan Koychev, Henrik Zetterberg, Robert Sugar, Augustinas Malinauskas, Khaled Saab, Hannah Madan, Jonathan C. M. Wan, Ravi Solanki, 2025. bioRxiv 2025.07.16.665231. - Early detection of multiple cancer types using multidimensional cell-free DNA fragmentomics [link]

Hua Bao, Shanshan Yang, Xiaoxi Chen, Guangqiang Dong, Yuan Mao, Shuyu Wu, Xi Cheng, Xuxiaochen Wu, Wanxiangfu Tang, Min Wu, Shiting Tang, Wenhua Liang, Zheng Wang, Liu Yang, Jiaqi Liu, Tao Wang, Bingzhong Zhang, Kuirong Jiang, Qin Xu, Jierong Chen, Hairong Huang, Junjie Peng, Xiaomeng Xia, Yumei Wu, Shun Xu, Ji Tao, Li Chong, Dongqin Zhu, Ruowei Yang, Shuang Chang, Peng He, Xiuxiu Xu, JinPeng Zhang, Yi Shen, Ya Jiang, Sisi Liu, Xian Zhang, Xue Wu, Xiaonan Wang, Yang Shao, 2025. Nature Medicine 31:2737–2745. - Genome-wide cell-free DNA fragmentation in patients with cancer [link]

Stephen Cristiano, Alessandro Leal, Jillian Phallen, et al., 2019. Nature 570:385–389. - The Potential of cfDNA as Biomarker: Opportunities and Challenges for Neurodegenerative Diseases [link]

Şeyda Aydın, Seda Özdemir, Ahmet Adıgüzel, 2025. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience 75:34. - Cell-free DNA-based liquid biopsies in neurology [link]

Hallie Gaitsch, Robin J. M. Franklin, Daniel S. Reich, 2023. Brain 146(5):1758–1774. - DNA methylation signatures of Alzheimer's disease neuropathology in the cortex are primarily driven by variation in non-neuronal cell-types [link]

Gemma Shireby, Emma L. Dempster, Stefania Policicchio, et al., 2022. Nature Communications 13:5620. - Function and information content of DNA methylation [link]

Dirk Schübeler, 2015. Nature 517:321–326. - Cell-free DNA comprises an in vivo nucleosome footprint that informs its tissues-of-origin [link]

Matthew W. Snyder, Martin Kircher, Andrew J. Hill, Riza M. Daza, Jay Shendure, 2016. Cell 164(1):57–68. - A DNA methylation atlas of normal human cell types [link]

Netanel Loyfer, Judith Magenheim, Agnes Peretz, et al., 2023. Nature 613:355–364. - Single-cell DNA methylation and 3D genome architecture in the human brain [link]

Wei Tian, Jingtian Zhou, Anna Bartlett, Qiurui Zeng, Hanqing Liu, Rosa G. Castanon, Matthew Kenworthy, Jordan Altshul, Cynthia Valadon, Andrew Aldridge, Joseph R. Nery, Huaming Chen, Jie Xu, Nathan D. Johnson, Jacinta Lucero, Julia K. Osteen, Nora Emerson, Johanna Rink, Junhao Lee, Yang Eric Li, Kimberly Siletti, Michelle Liem, Nicholas Claffey, Callum O'Connor, Alyssa M. Yanny, Julie Nyhus, Nick Dee, Tamara Casper, Natalia Shapovalova, Daniel Hirschstein, Song-Lin Ding, Rebecca Hodge, Boaz P. Levi, C. Dirk Keene, Sten Linnarsson, Ed Lein, Bing Ren, M. Margarita Behrens, Joseph R. Ecker, 2023. Science 382(6667):eadf5357. - Batchtopk sparse autoencoders [link]

Bart Bussmann, Patrick Leask, Neel Nanda, 2024. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.06410. - Artificial intelligence and circulating cell-free DNA methylation profiling: Mechanism and detection of Alzheimer's disease [link]

Ray O. Bahado-Singh, Uppala Radhakrishna, Juozas Gordevičius, Buket Aydas, Ali Yilmaz, Faryal Jafar, Khaled Imam, Michael Maddens, Kshetra Challapalli, Raghu P. Metpally, et al., 2022. Cells 11(11):1744. - Circulating Cell-Free DNA Methylation Profiles Enable Disease-Specific Detection of Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and ALS from Blood [link]

Chad Pollard, Erin Saito, Ryan Miller, Isaac Sirland, Mykle Keni, Andrew Jenkins, Jonathon T. Hill, Tim Jenkins, 2025. medRxiv 2025.10.07.25337503.

Citation

Wang, N., et al., "Using Interpretability to Identify a Novel Class of Biomarkers for Alzheimer's Detection", Goodfire and Prima Mente, 2026.

@article{wang2026alzheimers,

title={Using Interpretability to Identify a Novel Class of Biomarkers for Alzheimer's Detection},

author={Wang, Nicholas and Fang, Ching and Bissell, Mark and Hazra, Dron and Pearce, Michael and Nalmpantis, Christoforos and Niki, Pouya and Kathail, Pooja and Karailiev, Andrey and Ganbat, Javkhlan-Ochir and Giacomoni, Luca and Wan, Jonathan and Solanki, Ravi and Jain, Archa and Balsam, Daniel},

year={2026},

month={January},

day={28},

note={Goodfire and Prima Mente collaboration},

url={https://www.goodfire.ai/research/alzheimers-biomarkers}

}