Features as Rewards: Using Interpretability to Reduce Hallucinations

Contents

In our recent essay on intentional design, we described a vision for using interpretability to guide model training — moving from guess-and-check to closed-loop control. Our new paper introduces our first concrete demonstration of that vision: using lightweight probes on a model's internal representations as reward signals for reinforcement learning, applied to the problem of reducing hallucinations. We call this approach RLFR: Reinforcement Learning from Feature Rewards.

Our results show that RLFR is both effective in terms of reducing hallucinations without off-target effects, and retains the ability to use the probe as a monitor at test time, which unlocks strong test-time scaling performance. Quantitatively, RLFR reduces hallucinations in Gemma-3-12B-IT by 58% (when run with our probing harness), at ~90× lower cost per intervention than the LLM-as-judge alternative, with no degradation on standard benchmarks. You can explore some samples in our interactive viewer here.

Why is it hard to fix hallucinations?

Teaching a language model not to hallucinate is harder than it sounds. The core difficulty is supervision: how do you provide a training signal for whether a given claim is true?

For tasks with verifiable answers, such as math or coding problems, reinforcement learning has made impressive strides. In these cases, the reward follows deterministically and quickly from the suggested solution (e.g., the unit tests pass). Hallucinations, on the other hand, are harder to verify at scale. Checking whether a model's claim about, say, a historical figure's biography is accurate requires either a human with domain expertise or a tool-augmented LLM doing web search. Both are too slow and costly to serve as reward signals at the scale RL requires. Furthermore, if you want to teach a model to not only recognise hallucinations, but also to correct them, then you need to determine if the proposed correction is good - an even harder task!

The difficulty of providing feedback on hallucinations creates a bottleneck. The behaviors we most want to improve - factual accuracy, calibrated uncertainty, honest acknowledgment of knowledge limits - are precisely the ones where supervision is most expensive.

These are examples of “open-ended tasks”: tasks where precise verification of the ground truth is either too expensive or infeasible. Hallucinations are a particularly important example of this class of problems, as they are a well-known problem for language models, and one that considerable effort is spent to fix. This makes them a challenging testbed for our methods: if we succeed here, we have reason to believe that the technique will transfer to other open-ended problems.

Our approach

Probe pipeline: detecting hallucinations in complex long-form responses

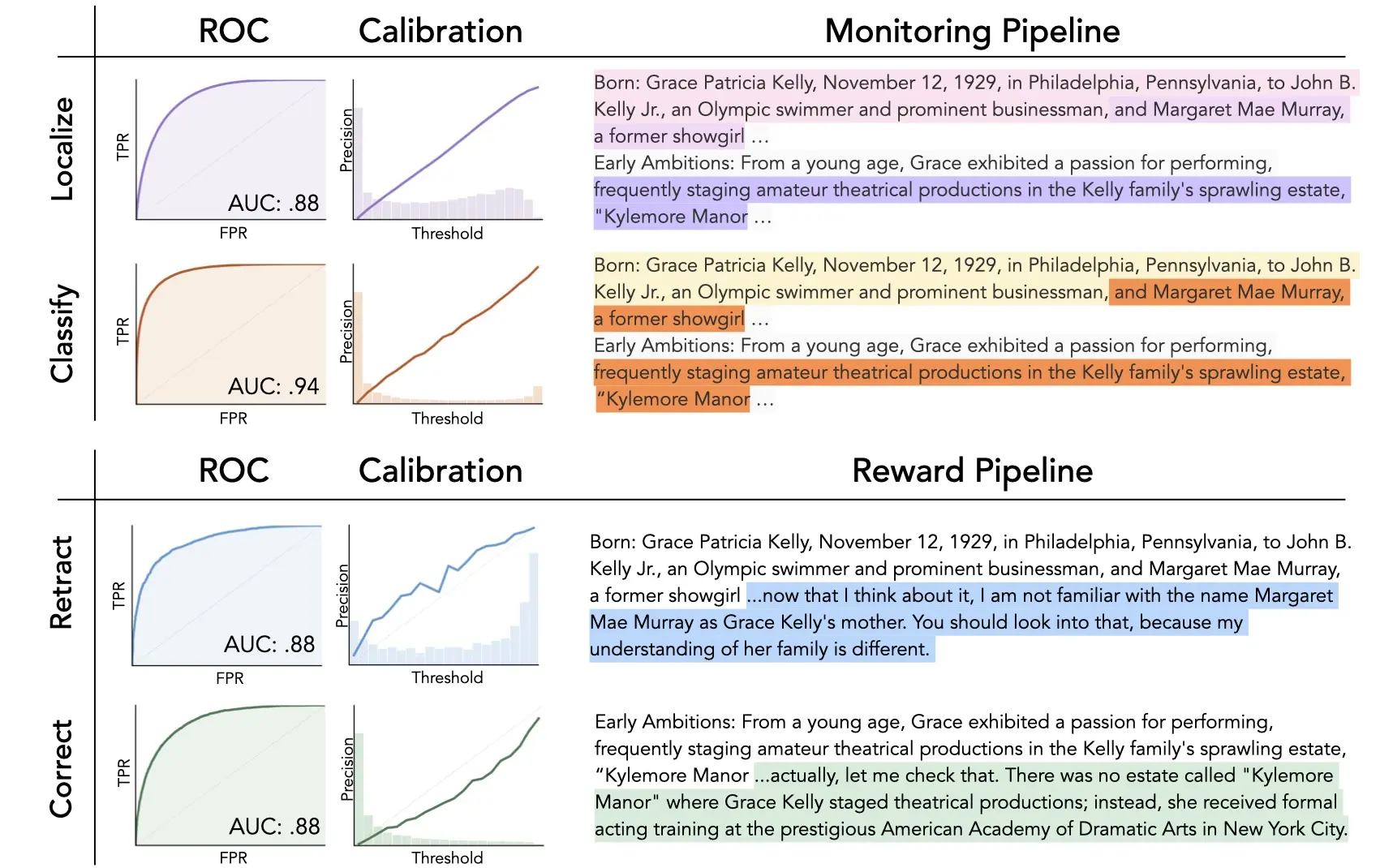

Our approach makes use of a surprising source of information: the model's own activations. We train a series of probes to identify factual claims, classify them as true or false, and then classify corrections and retractions as successful or unsuccessful.

First, we curate a dataset of rollouts from Gemma on a range of factually-dense prompts from the Longfact++ dataset, along with labels from Gemini 2.5 (+ web search), including both true and false on-policy factual claims and example corrections and retractions of erroneous claims. We use this dataset to train our probes.

The probes underpin a pipeline for identifying and correcting hallucinations, which has four stages:

- A token-level localization probe identifies candidate entity spans in the model's output - the specific claims that might be hallucinated.

- A span-level classification probe classifies whether each entity is a hallucination.

- When the classification probe flags a hallucination, the policy generates an inline correction or retraction. The model samples multiple candidate interventions — corrections that replace the hallucinated claim with an alternative, or retractions that acknowledge the claim may be unreliable.

- Finally, two additional reward probes grade the quality of these interventions. (One probe grades corrections, and the other grades retractions.) These probe scores become the reward signal for RL training.

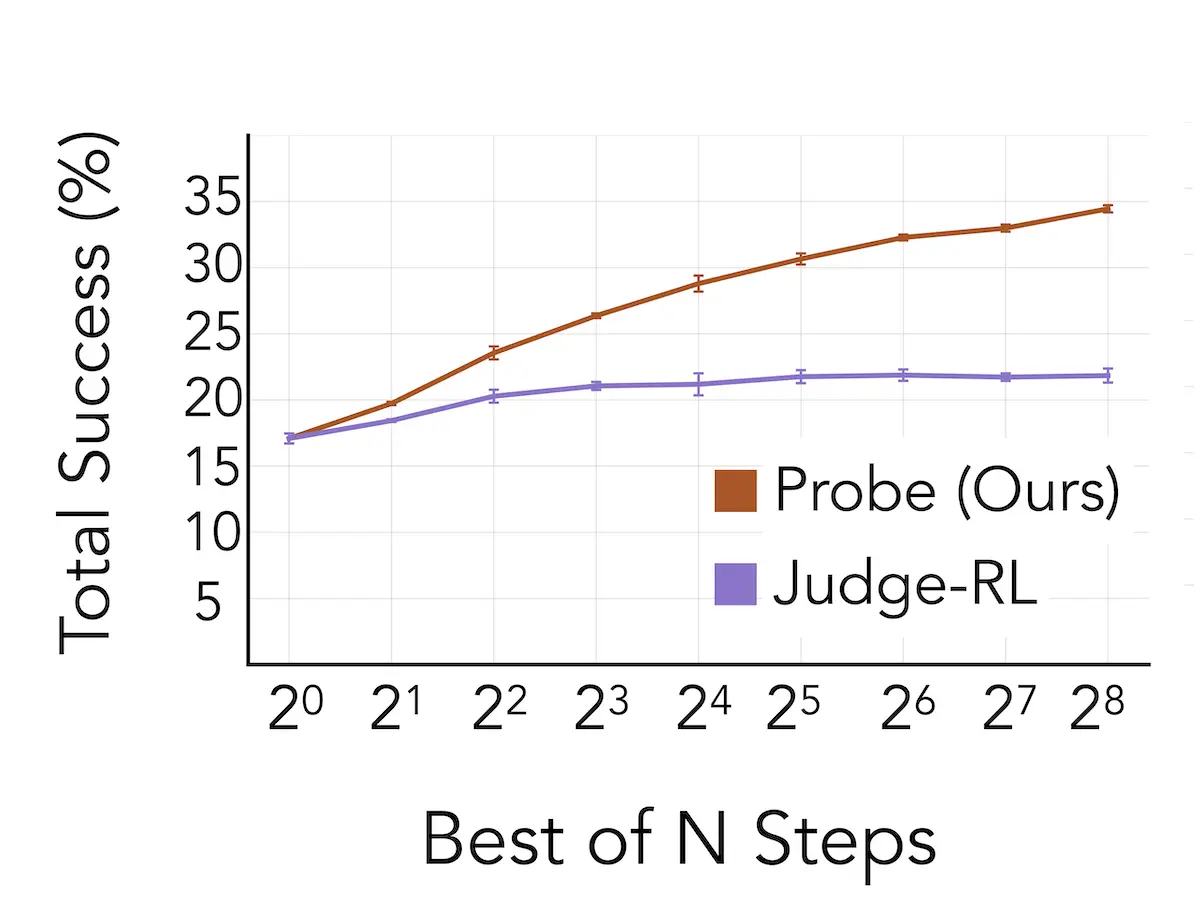

Because our probes have high predictive power, we can amortise the time and expense of fact-checking into one training run of a probe, which we can then run quickly and cheaply during RL training. Our probes also enable test time scaling (more on this later).

At first glance this might seem impossible! Where does the information come from, and why doesn't the model already use it? Prior work (e.g., Orgad et al.) shows that model internals carry important signals about hallucinations that don't appear to be properly used by the model, similarly to our results on detecting personally identifiable information. We go into some potential reasons that this approach succeeds in a later section, but the empirical success of our approach speaks for itself.

RL setup

We train the model in a standard RL setup using the reward probes, which are run on a frozen copy of the model, not the student's activations. This allows us to scale training without the student learning to evade our monitors.

We train for approximately 360 optimizer steps at a cost of roughly $2.5k. For comparison, if we used our LLM judge (Gemini 2.5 Pro with web search) as a reward signal with the same budget, we would only get through 3–5 steps of training.

Our RL setup uses standard algorithms (adapted from ScaleRL with CISPO); our main innovation is in the source of supervision signal. We therefore expect that this approach will benefit from future improvements in RL.

Results: reducing hallucinations with RLFR

We evaluate RLFR on LongFact++, a dataset of approximately 20,000 knowledge-intensive long-form generation prompts spanning eight domains: biography, science, medical, history, geography, citations, legal, and general. We hold out 999 prompts as a test set.

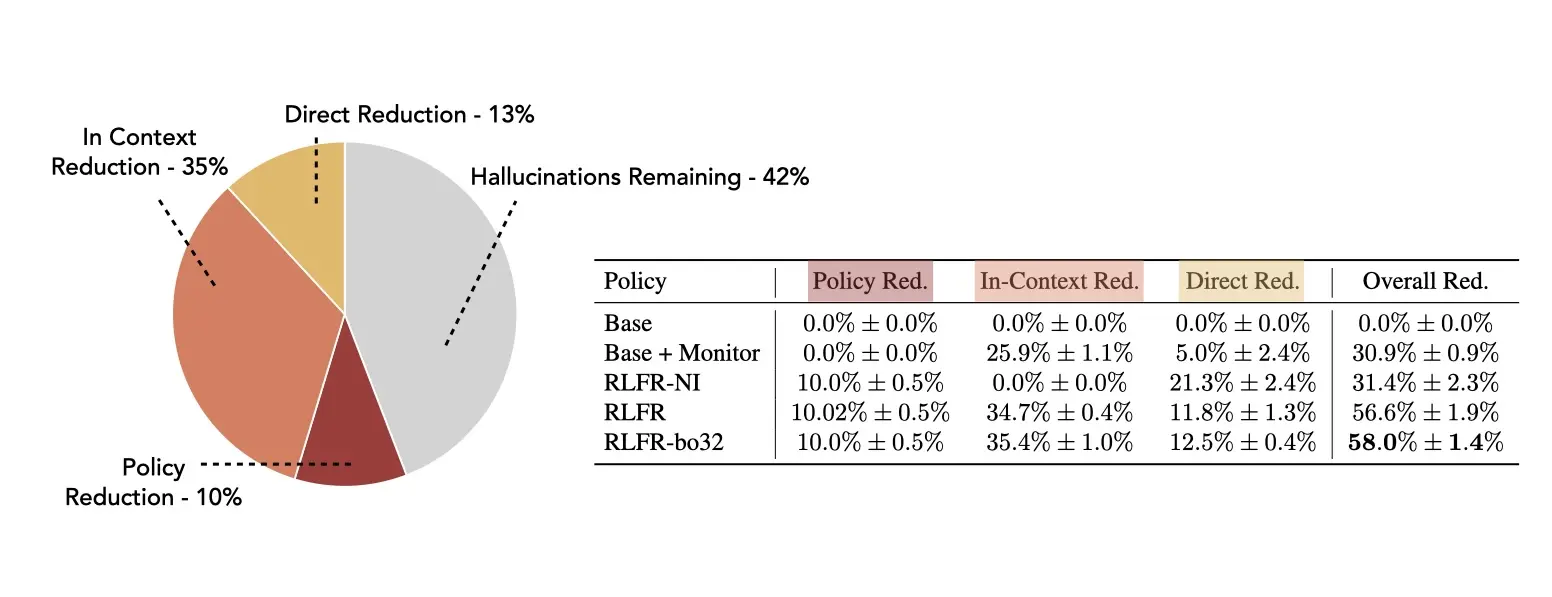

Overall, we reduce the hallucination rate by 58% across the held-out test set. This overall reduction comprises improvements in the policy itself, in-context learning effects, test-time monitoring and intervention, and test-time scaling using our probing setup.

We can decompose the reduction in hallucinations to understand where the improvements in the system are coming from.

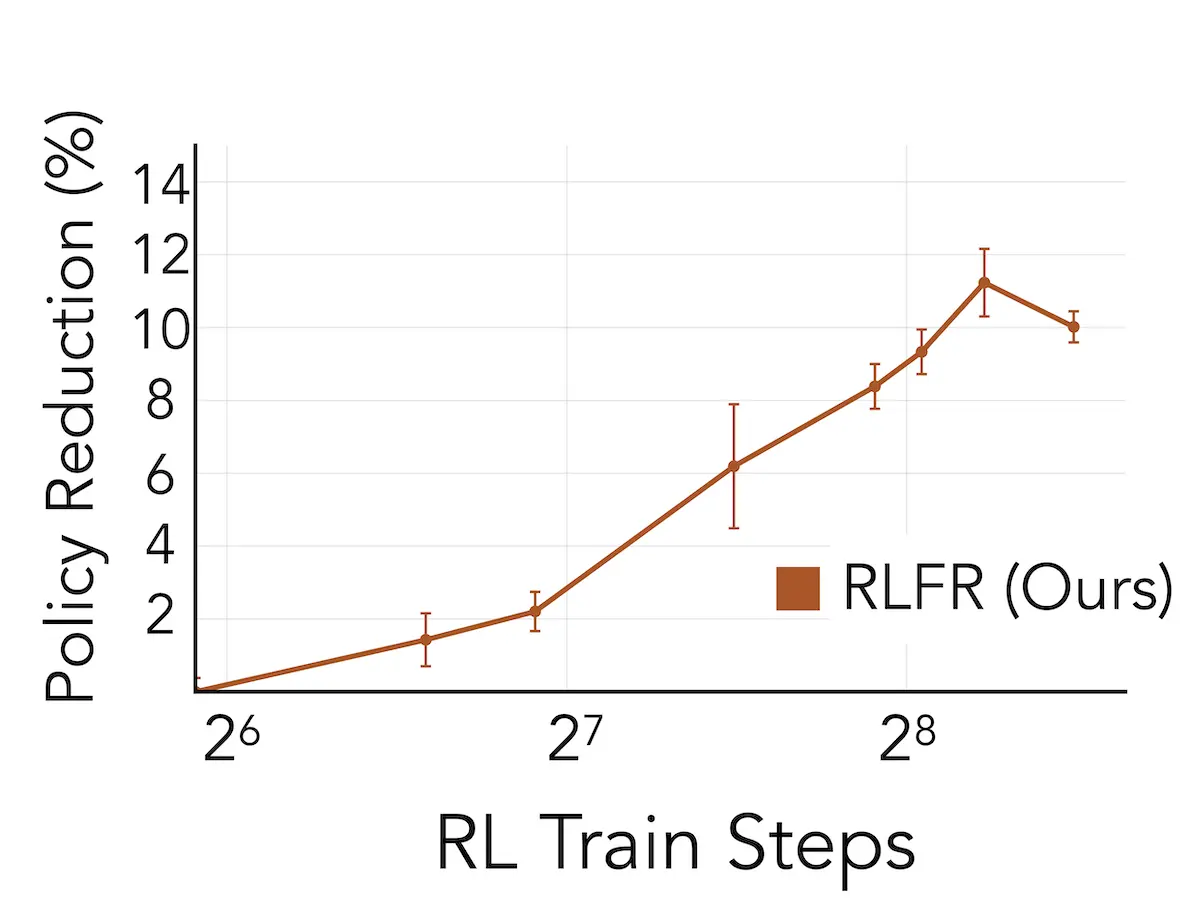

The cleanest form of improvement is what we call policy reduction, which accounts for 10% of the total. After RLFR training, the model itself generates fewer hallucinations and becomes inherently more cautious about unsupported claims; the model's underlying behavior has changed.

The largest contributor is in-context reduction, at 35%. Inserting corrections and retractions inline helps the model avoid compounding errors in subsequent generation. When the model corrects an early hallucination, downstream claims that would have built on that hallucination are avoided. Additionally, inline interventions might be updating model “beliefs”, pushing the policy towards factuality more generally. For more discussion, see our full paper. This is a large source of reduction, and we should note that some of it comes from just the structural decision to insert interventions inline rather than from intervention quality: the base model with inline prompts achieves a 24.9% in-context reduction even without RLFR training.

The remaining 12.5% comes from direct reduction — the net effect of interventions actually fixing (correcting or retracting) individual hallucinations.

Why should this work?

If the model already “knows” this information, why doesn't it use it? There are a few possible reasons:

- The model may not be confident that the task being performed is correct factual recall. This might seem strange, but common tasks we ask language models to perform such as fiction writing make use of a model's capability to make things up.

- Current post-training pipelines might reward fluent and confident hallucination over other outcomes, particularly because fact-checking is hard to incorporate into a practical RL loop for all the reasons given earlier.1Both of these first two possibilities come down to a change in “beliefs”: we have to make the model more confident that what we want truly is factually correct generations, but current methods give us a limited set of ways to convey that preference.

- A model's mechanisms for checking a fact might occur prior in the model to the mechanisms for generating factual claims, and not well “wired up” to the output to change behaviour in the ways we want.

This is almost certainly not an exhaustive list, and we expect deeper interpretability investigations to unearth more detail (we'd love to hear from you if you have any additional results to share).

Furthermore, the test-time scaling results are surprising. A common concern with optimising against the signal from a probe (as we do here) is that the model will simply learn to change its representations rather than its behaviour, removing the probe as a source of information at some later point. In this work we demonstrate that not only does this not occur in our setup in spite of substantial optimisation - changing behaviour turns out to be far easier than changing representations - the probe signal is sufficiently robust that we can actually use it for further optimisation at test time.

RLFR and intentional design: interpretability in training

RLFR is the first work we're sharing from our research agenda of intentional design — the science and technology that lets us guide model training.

In his recent post about intentional design, our Chief Scientist Tom articulated the general principle of “not fighting gradient descent” while leveraging interpretability in training. This is the case with our setup here: the probes observe and evaluate, but the training updates flow through the standard RL objective. Since the gradient cannot flow through the probes — since they are run on a frozen copy of the base model during training, not on the student — the student learns to produce tokens that score well on the probes, rather than activations that hack them. And as discussed above, the fact that the probe signal remains useful even after substantial training — enough to drive test-time scaling — is evidence that this approach is working as intended.

The probe transfer result reinforces this. Our reward probes were trained on activations from the base model, but they work equally well when run on the trained policy's activations. This has a practical benefit — you don't need to host both the base and trained models at inference time — but it also matters for the vision Tom lays out in his essay, regarding interpretability as a “test set” for model behavior. If probes trained on one version of a model remain valid on a different version, it suggests that the representations being read are more stable than you might fear.

This is only a first data point, but it's an encouraging sign for the idea that we can use certain interpretability techniques during training without the training process undermining interpretability's usefulness for evaluation and monitoring.

RLFR sits at an early point on the intentional design tech tree. The probes here are reading relatively specific signals - entity-level hallucination detection - and feeding them into a standard RL loop. We are developing techniques as part of a more ambitious vision for guiding gradient descent and translating natural language into targeted weight updates. That vision will require further algorithmic innovations, but these results establish an important prerequisite: interpretability can enable effective training-time supervision.

Read the full paper for complete technical details, including probe architectures, data collection methodology, RL training configuration, and extended evaluation results, as well as a full list of references.

References

For a list of references, please see the full paper.

Citation

Please cite the full paper.